PROCESSES

Visualizing African Student Mobility

What can bundles of worn index cards tell us about twentieth-century African migration to the United States? In 1959, Horace Mann Bond, then dean of the School of Education at Atlanta University, set out to survey the history of encounters between African Americans and Africans. Key to his investigation was his interest in African students who studied at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) in the US as early as 1848. Against the backdrop of desegregation at home and African decolonization abroad, Bond hoped to demonstrate what he deemed the underappreciated role of HBCUs in educating West African leaders such as Nnamdi Azikiwe (later the first president of Nigeria) and Kwame Nkrumah (the first president of Ghana). Drawing upon information provided by a vast network of fellow college administrators, Bond compiled over 1,100 index cards, each documenting information on an African student.1 These cards are a critical resource for my research on the religious, racial, and political formation of African students in the US during the twentieth century.

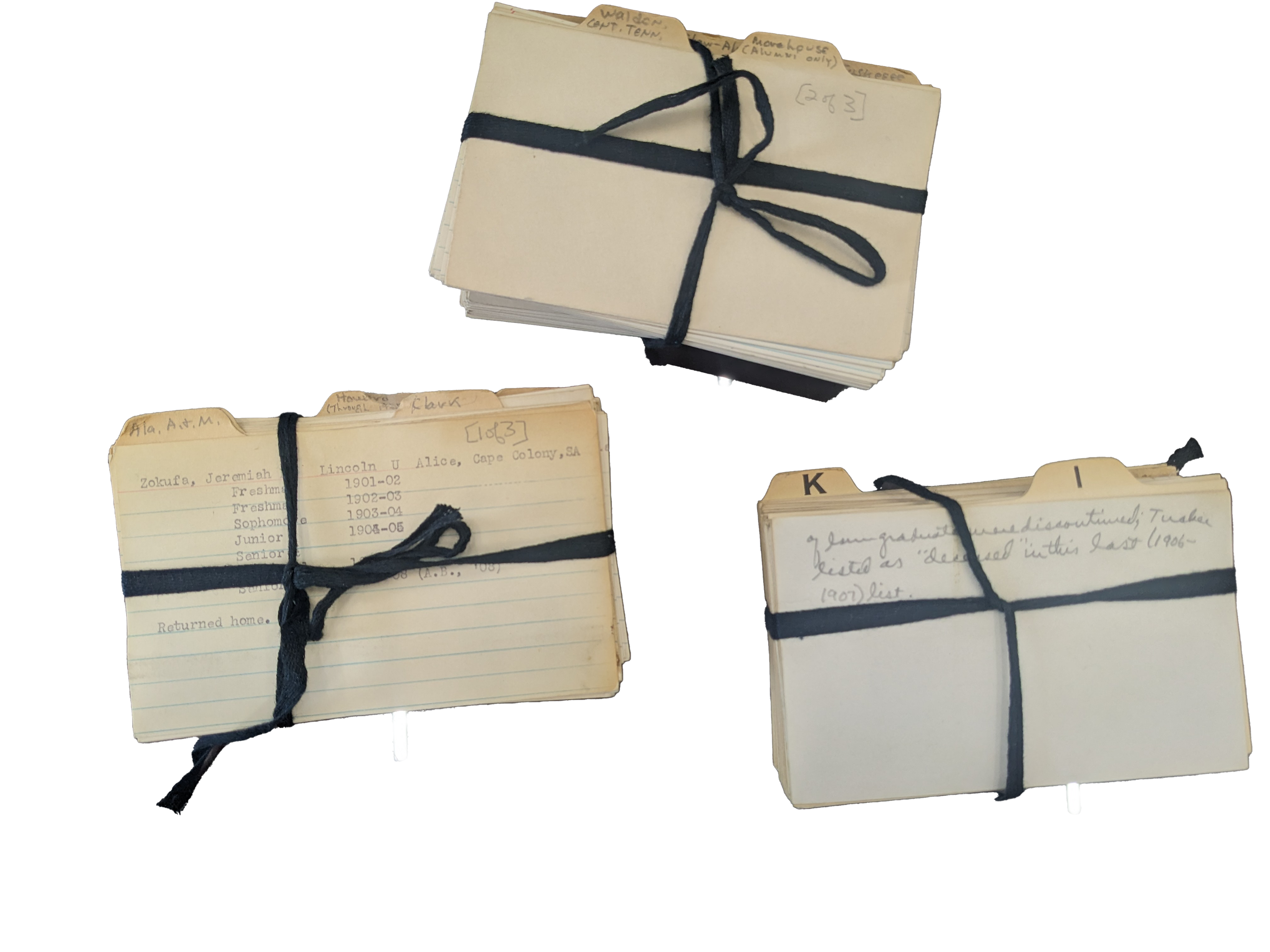

Figure 1. Sample Set of Index Cards. “African Students Survey: Index Cards,” 1961.Horace Mann Bond Papers, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, UMass Amherst Libraries. Photo taken by author.

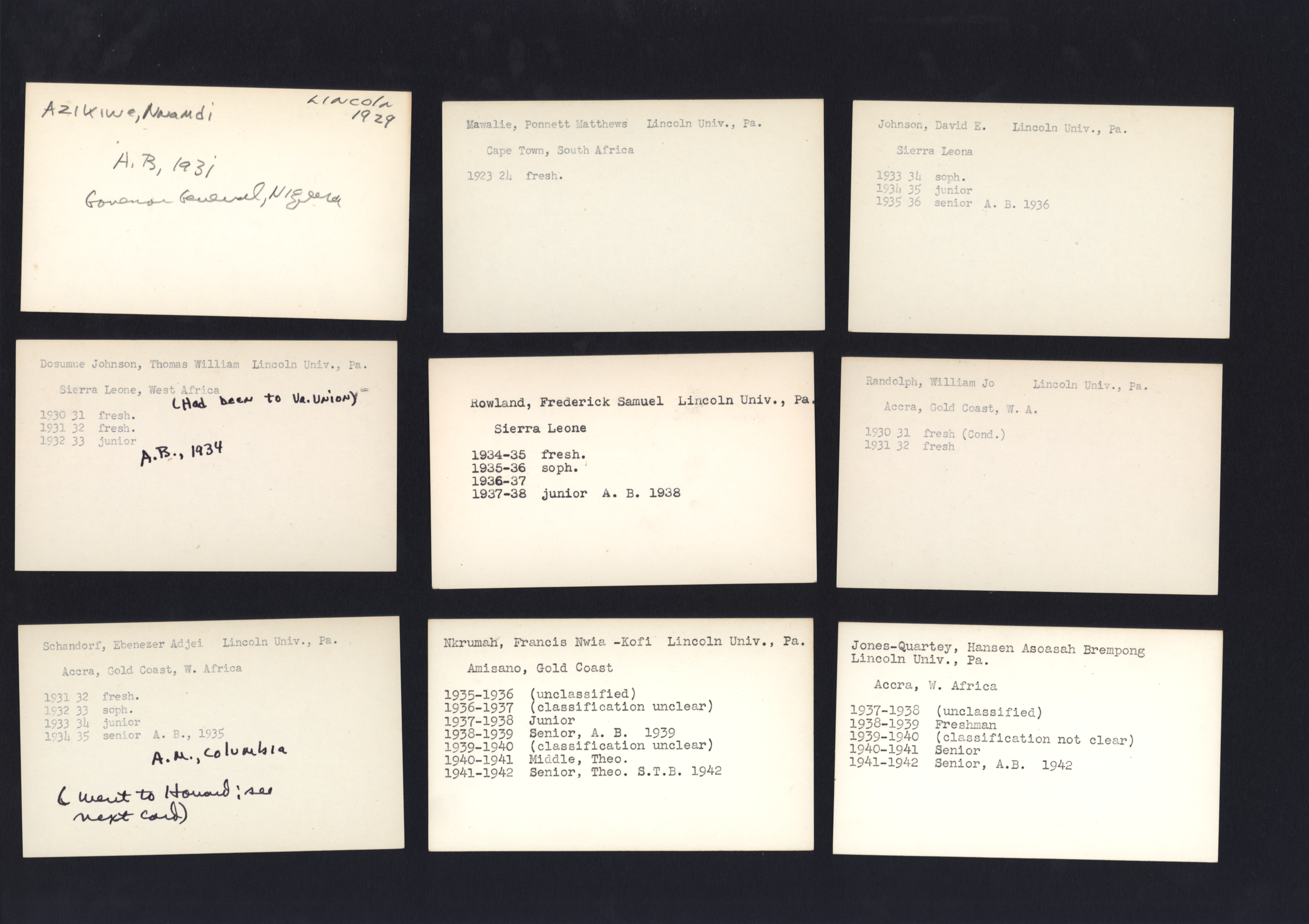

As a primary source for analyzing African student mobility, the index cards provide an unparalleled body of archival material that has yet to be analyzed by scholars. Spanning decades worth of data on student migration to over thirty HBCUs, the cards consist of the student’s name, where in Africa they came from, the college or university they attended in the US, and the years in which the student was enrolled at the school.2 Many cards also include miscellaneous notes such as the student’s area of study, whether they returned to Africa, or their occupation following graduation. Housed in a collection of Bond’s personal papers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, the cards offer portraits of students who attended HBCUs at various times, through various means, and for various purposes.

Handling the cards was just as intriguing as the information they possessed. For each of the thirteen bundles of cards, I carefully removed the black cord binding the cards together. Trying not to disturb the order of the cards, I slowly shuffled one bundle before moving to the next. I let my imagination wander as I speculated about the stories behind the names and details printed on each card. As I perused the cards, I grew convinced that analyzing the “transatlantic educational traffic” of twentieth-century African student mobility presented an exciting opportunity to contribute to the growing body of research that explores student migrations in the context of religion and geopolitics.3 Having located African students in this abundant archive, I hoped to situate them in both time and space.

Using a repurposed set of tabbed recipe card dividers, Bond roughly organized the index cards by educational institution.

There was just one problem: although the index cards presented a wealth of information, working with the data on the cards in their current form proved to be unwieldy. Using a repurposed set of tabbed recipe card dividers, Bond roughly organized the index cards by educational institution with clear sections separating African students who attended Lincoln University from those who attended Howard University, for example. This way of organizing the data was perfectly suitable for beginning to answer some of his driving research questions—questions that still preoccupy scholars of African student mobility: “Where did they come [from]? Why? Who sent them?”4 But what if you wanted to ask additional questions of Bond’s data? What if, like me, you were curious about how African student mobility might have changed over time?

Figure 2. Sample set of index cards. “African Students Survey: Index Cards,” 1961.Horace Mann Bond Papers, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, UMass Amherst Libraries. Photo taken by author.

While images of the index cards have since been digitized, the data remains frozen in time. The text on the cards, a mixture of typewritten and handwritten scripts, cannot readily be processed by text-recognition software.5 Furthermore, the scanned cards are still organized according to academic institution, thus obstructing other ways of conceiving and ordering the data. Without the ability to easily reorganize and visualize the information on the cards, the full potential of Bond’s intellectual labor has yet to be realized. Motivated to transform this static data into a more pliable form useful for my research, and hopefully that of others, I sought to build upon Bond’s work using digital tools.

Once I was armed with geographic data—that is, the locations where the students were from and the HBCUs they attended—my first inclination was to transform the information on the cards in order to produce a map. I wondered what viewing the scope of students’ trajectories might tell me about the nature and contours of their mobility. Fixated on this goal, I began my digital work by viewing it as a means to an end—a laborious, yet necessary chore needed to generate a final product. I assumed that the primary value of digital tools was their convenience. Perhaps, I thought, digital humanities approaches could help me more quickly get to the “true” work of scholarship by making it easier for me to study the information and arrive at scholarly conclusions. I decided my digital experiments would take three forms: transcribing the data, reorganizing the African student records by creating a database, and finally, visualizing African student migration to HBCUs through mapping.

The full potential of Bond’s intellectual labor has yet to be realized.

Yet, I soon realized that the process of creating the digital products was itself a practice of scholarly interpretation. The decisions I made along the way—from how to organize the material to what information to add to Bond’s dataset—reflected my efforts to make meaning of the data in ways that went beyond Bond’s interest in highlighting the significance of HBCUs. To be sure, digital tools, at times, provided a more convenient way of accessing and manipulating the data on the cards. However, working with the archival material using digital humanities methods was not simply a matter of ease. As a supplement to my archival work, using digital tools challenged me to deepen my scholarly inquiry and develop new approaches for analyzing African student mobility. My process revealed that mapping is not the end of our scholarly explorations, but, in many ways, the beginning.

The breadth of information Bond gathered is as remarkable now as it would have been then. Recent scholarship on twentieth-century African students in the US has typically relied on data representing students who hailed from one African country or region, students recruited by one US Christian denomination, or students funded by one governmental program.6 Historical records documenting African student mobility are as far-flung as the students themselves, often limiting opportunities to identify broader trends in factors that might have informed students’ trajectories. However, thanks to Bond’s meticulous data curation, we now have access to hundreds of names of African students—individuals who otherwise would have remained buried in the past and within scattered archival records. The index cards thus provide one of the most extensive pieces of historical evidence documenting African migration to the US during the twentieth century.

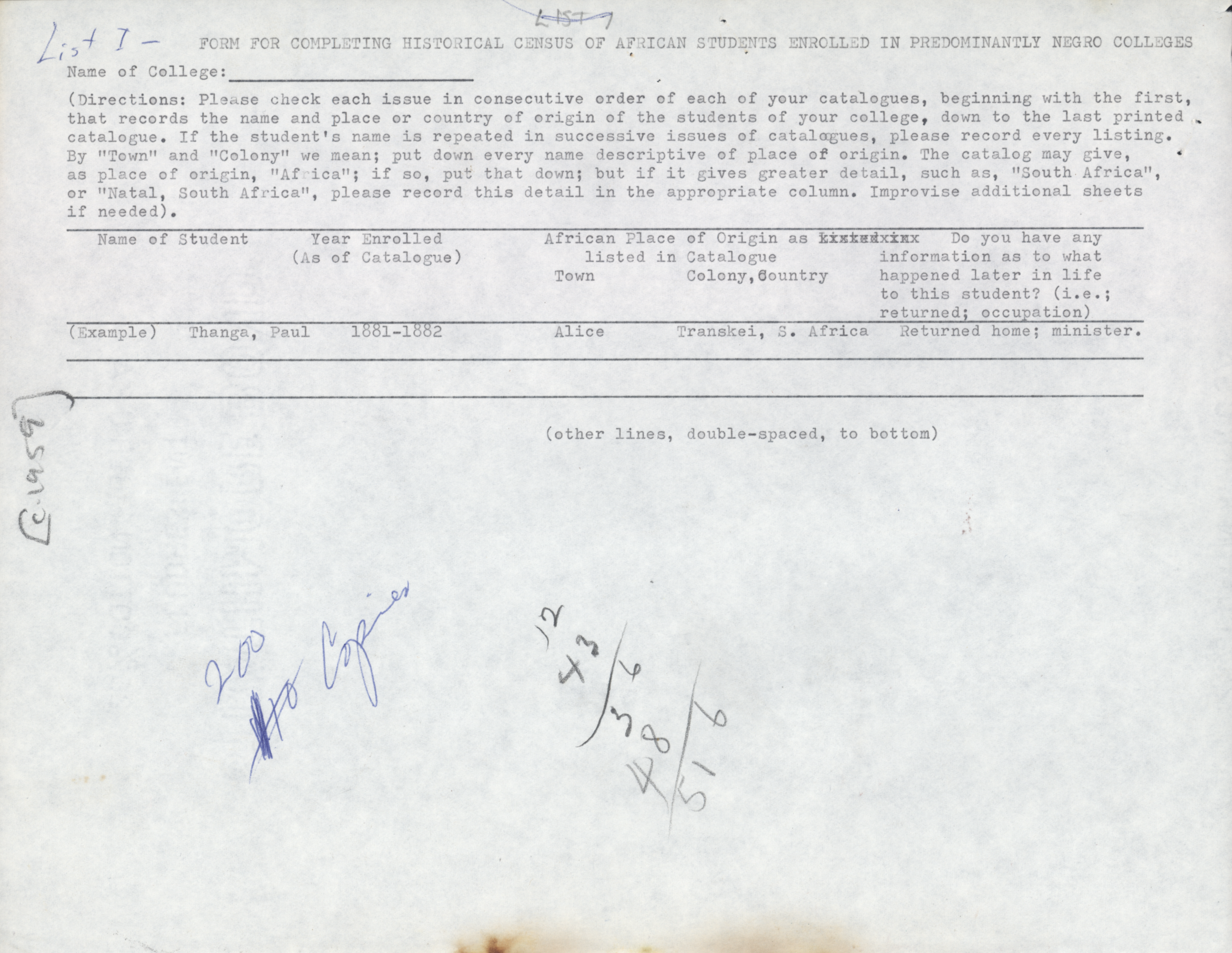

During his term as president of Lincoln University, Bond developed a keen interest in learning about African students who came to the US. As the first African American president of the Pennsylvania institution, he inherited Lincoln’s long-standing commitment to educating Black men from Africa and the African diaspora. Founded in 1854 with a mission oriented toward “the redemption of Africa,” Lincoln (then called the Ashmun Institute) had enduring, if not complicated, religious connections to the continent.7 In 1959, Bond began conducting a “historical census” of the African presence at HBCUs. With financial support from the United Negro College Fund, he wrote to over twenty registrars and deans to assist in collecting the data.8 The information would serve as the basis for his discussion of Lincoln’s legacy of educating Africans as documented in Bond’s history of Lincoln entitled Education for Freedom.9

Figure 3. Form for completing historical census of African students, ca. 1959.Horace Mann Bond Papers, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, UMass Amherst Libraries.

After viewing the above form, I transcribed the information on the cards into a spreadsheet using Bond’s original categories as a structural guide, beginning with the following columns: “Name,” “Institution,” “Years Enrolled,” “African Hometown,” “African Country of Origin,” and “Miscellaneous Notes.” The slow work of transcribing the text on the index cards exposed the limitations of these categories. Modifications would need to be made to account for the variability of data found on the cards. I aimed to transform the spreadsheet into a database that was more than a mere reflection of Bond’s institutional concerns and instead could be useful for my research questions. Inspired by the work of Black digital humanities scholar, Kim Gallon, I hoped the digital database could be used as a “technology of recovery” to begin unearthing the narratives of African students.10 Further engagement with the archival material using digital tools offered opportunities to arrive at new ways of interpreting Bond’s data—to tell new stories.

The process of reorganizing and visualizing the information on Bond’s index cards came with its own set of difficulties. I soon realized, as other scholars have observed, that digital humanities approaches do not simply “do our work for us,” but instead “point to where our work lies.”11 One of the first modifications needed was to account for students who attended more than one academic institution during their stay in the US. After transcribing the data, and with the assistance of the data-cleaning software OpenRefine, I discovered that about one-fourth of the cards were duplicates. What began as a database with about 1,150 entries was whittled down to a collection of 860 entries. I soon realized that many African students began their education at one institution in the US and transferred to other schools to complete their undergraduate education or to pursue graduate or professional training. The data on the index cards does not always document these movements. Still, we can see that the internal mobility of African students in the US meant that some appeared in the records of multiple institutions, thus generating multiple cards that highlight different segments of a student’s educational journey. As a result, the “Institution” category spawned two additional columns. For at least sixteen percent of students, their first stop in the US was not their last.

| ID | Duplicate ID | Name | Africa City | Africa Country | Education Record Start | Education Record End | Institution 1 | Institution 2 | Institution3 | Misc. Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 00055 | 00676 | Nurse, Nathaniel | Monrovia | Liberia | 1876 | 1879 | Fisk University | NA | NA | Studied theology; Sent to Fisk by friends in London for missionary work; Returned to the Mendi Mission in West Africa |

| 01081 | NA | Aggrey, James Emman | Cape Coast | Ghana | 1898 | 1902 | Livingstone College | NA | NA | Faculty and Financial Secretary at Livingstone College 1903—1904 |

| 00934 | “00284, 01045” | Tantsi, Harsant J.J. | Lesseyton | South Africa | 1898 | 1906 | Wilberforce University | Morris Brown College | NA | Studied carpentry and vocal music; 1915—1917 Minister in South Africa |

| 00237 | 00899 | Mdodana, David Buyabuye | Idutywa | South Africa | 1906 | 1909 | Shaw University | NA | NA | Graduated with B.Th. in 1908 |

| 00346 | 00217 | Langa, Arthur Bidewell | Mtwalume | South Africa | 1912 | 1913 | Lincoln University | NA | NA | Freshman; Remained for only one year |

| 00352 | NA | Azikiwe, Benjamin Nnamdi | Missing | Nigeria | 1927 | 1932 | Lincoln University | Howard University | NA | Lincoln A.B. in 1931 |

| 00359 | NA | Nkrumah, Francis Nwia-Kofi | Amis[s]ano | Ghana | 1935 | 1942 | Lincoln University | NA | NA | A.B. in 1939; S.T.B. in 1942 |

| 00051 | “00680, 01061” | Massaquoi, Fatima Sandimanni | Monrovia | Liberia | 1936 | 1942 | Fisk University | Lane College | NA | M.A. in 1941; Daughter of another Massaquoi (Albert Momo Thompson) |

| 01052 | 00727 | Hammond, Samuel Ashitey | Accra | Ghana | 1948 | 1956 | Morris Brown College | Atlanta University | NA | Studied English at Morris Brown; Graduate student in social sciences at Atlanta University |

| 00149 | “00142, 00982 " | Gibson, Joseph | Freetown | Sierra Leone | 1952 | 1957 | Central State College (Wilberforce) | NA | NA | Studied theology |

| 00871 | NA | Okwumabua, Onuekwuke | Iselle-Uku | Nigeria | 1956 | 1957 | Virginia Union University | NA | NA | Student in the School of Drama |

Adjudicating the duplicate student entries proved to be one of the most exciting, though laborious, aspects of the reorganization process. Some duplicate entries were indeed due to students attending multiple institutions while others were due to the misspelling of student names. In order to clean the duplicate entries, I turned to additional archival materials. Doing so exposed me to a range of archival sources, allowing me to locate African migrants in unexpected places. Using archival databases such as Ancestry, I searched the names of students who had multiple cards. University yearbooks, immigration records, US census data, World War I and II draft registration cards, naturalization documents, and other historical records became my guide for placing students in time and space. In my field of religious studies, such sources have been underutilized by scholars of African migration who have typically relied on ethnographic methods in their studies of contemporary African migrant communities.12 Triangulating historical sources allowed me to wade through hundreds of duplicate index cards while also beginning to flesh out the narratives of twentieth-century African students.

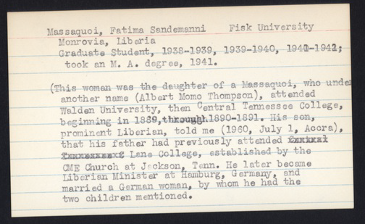

Figure 5. One of Fatima Massaquoi’s index cards.Horace Mann Bond Papers, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, UMass Amherst Libraries.

Liberian student Fatima Massaquoi, who first appears in HBCU catalogs in 1936, for example, attended two Tennessee HBCUs—Lane College and Fisk University—and thus has two sets of index cards. Fatima was not the first in her family to study at an HBCU. Her father, Momolu Massaquoi, attended the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church’s Central Tennessee College (later called Walden University) in 1888. Unlike some African students whose travels were sponsored by their home governments, US immigration port records show that the Massaquoi family was able to self-fund Fatima’s journey to the US. Fatima began her US education at Lane, which was then led by a former classmate of her father’s. After completing her studies at Lane, Fatima decided she wanted to pursue graduate work in sociology. Unfortunately, Lane did not have such a program at the time, so she enrolled at Fisk. Fatima, like many other students, began her studies at an institution where she had relational connections and later continued her studies at institutions that were better suited for her academic interests. Although Bond hoped to highlight the contribution of HBCUs to African students’ educational formation, my study of Fatima’s record suggests that African students also played a pivotal role in “shaping the nature, meaning and scope of their mobility” by attending multiple institutions.13 As one of the relatively few African women who studied in the US during the twentieth century, Fatima’s presence in archival records also invites scholars to consider the role of gender in mediating the migratory experiences of African students.14

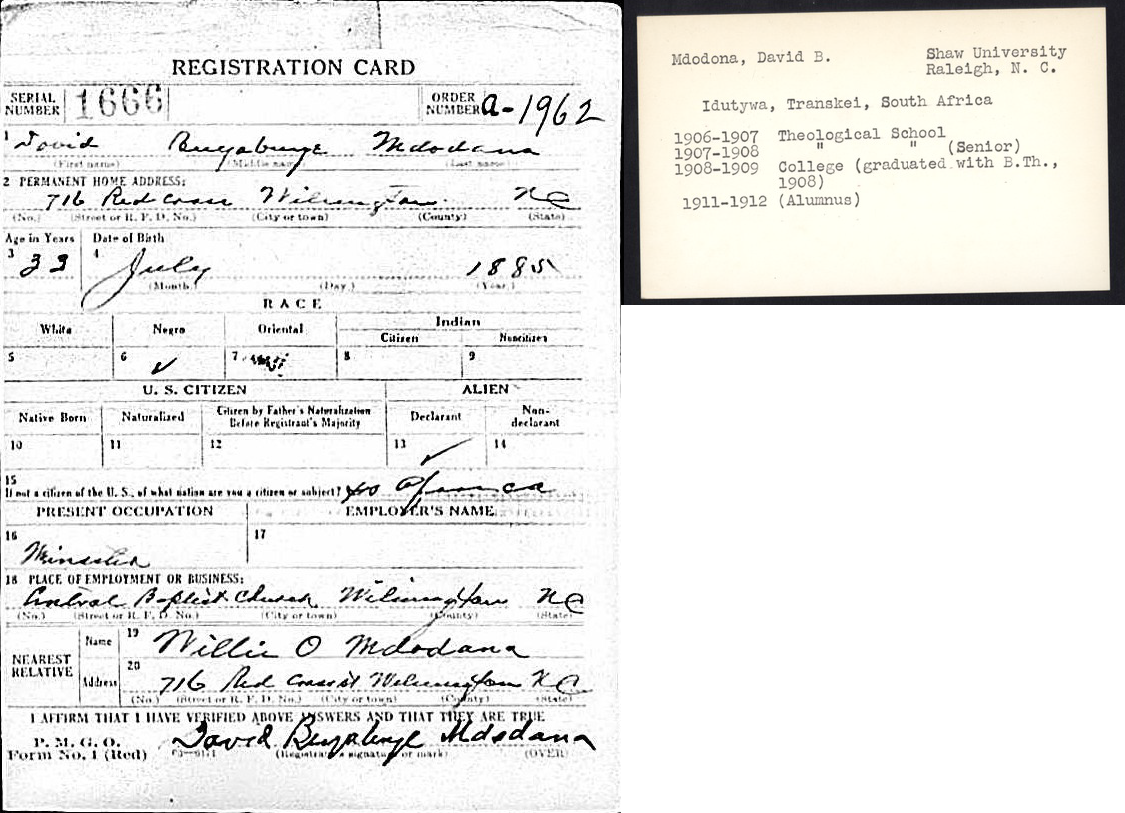

Figure 6. (Left) David Mdodana’s World War I Draft Registration Card. Ancestry.com, World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917—1918. (Right) One of David Mdodana’s index cards. Horace Mann Bond Papers, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, UMass Amherst Libraries.

South African student David Mdodana also appears twice in Bond’s set of index cards, although his last name is misspelled as “Mdodona.” Both cards place Mdodana at Shaw University around the same time. The North Carolina HBCU was founded by the American Baptist Home Mission Society. I sought out additional historical records to confirm that the cards represented the same student and to see what else I could learn about him. Archival records reveal that he was among the eighteen percent of foreign-born men drafted into World War I.15 It does not appear that Mdodana fought in the war; however, his World War I draft card, available on Ancestry, does give us insight into his life in the US. The draft card lists Mdodana as a Baptist minister in North Carolina. One wonders how Mdodana might have made meaning of his conscription given his standing as a Black African “declarant alien”—one intending to become a citizen of the US. As a US-educated clergyperson, Mdodana joined other African students like Ghana’s James Aggrey who contributed to US religious life through their professional service.16

Fatima’s presence in archival records invites scholars to consider the role of gender in mediating the migratory experiences of African students.

Sorting through duplicates thus became one way to dive deeper into the lives of lesser-known students. Much ink has been spilled examining the lives of African students such as Nnamdi Azikiwe and Kwame Nkrumah—both statesmen and graduates of Lincoln University. However, my research suggests that plenty of work remains to develop a more robust understanding of African student mobility beyond the narratives of notable political figures. Given my interest in the religious formation of students, future versions of the database will include columns for the religious affiliations of the various HBCUs using additional archival material from Bond’s collection. As my digital work continues to develop, I hope to explore what connections might emerge between the religious affiliations of the students during their time in Africa and the religious affiliations of the institutions they attended while in the US. Doing so could illuminate the narratives of students who may not have had a significant political impact, but instead bridged religious communities in the US and Africa.

While preparing my data for mapping, I started to pay closer attention to where students came from. Given the temporal range of Bond’s study, covering the period of 1848–1960, the names of some of the students’ home countries changed over time. For example, students hailing from the “Gold Coast” gave way to students coming from “Ghana” when the country gained both independence and a new name in 1957. Moreover, the names of territories listed in the data such as “Congo Free State” (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), Tanganyika (Tanzania), and Nyasaland (Malawi), which are not found on present-day maps, also reflect Africa’s colonial history. Moving from transcription to mapping revealed that the search for African “origins,” even when equipped with geographic data, remains a contested endeavor.

Mapping is not the end of our scholarly explorations, but, in many ways, the beginning.

Reorganizing the data in this way also raised several questions that I hope to explore in my future research. For example: did the ebb and flow of various African independence movements influence how and whether African students articulated national identities while living in the US? Although this question cannot be answered with the index card data alone, it comes into view when restructuring the data and considering the broader implications of Africa’s shifting political landscape.

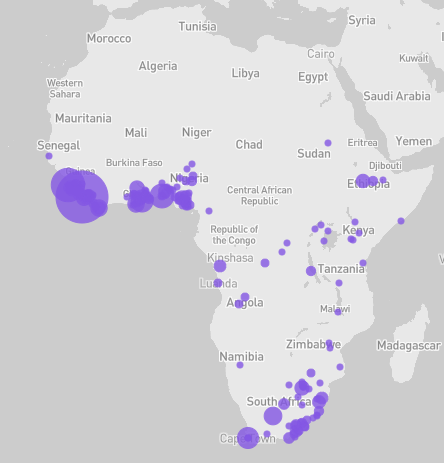

Figure 7. Hometowns of HBCU-educated African Students, 1848–1960.Generated by the author using Palladio.

Mapping the trajectories of African students who studied at HBCUs reveals the scope and dynamic nature of African migration during the twentieth century. Stanford University’s data visualization platform, Palladio, proved especially helpful in this regard. From 1848–1960, the majority of the approximately 865 African students who attended HBCUs came from five countries: Liberia, Nigeria, South Africa, Sierra Leone, and Ghana.17 Although African students during the twentieth century also migrated to places like Britain, France, and the USSR for higher education, the US was also an attractive option for at least two reasons. First, students from Anglophone African contexts studied in the US because of linguistic similarities. Second, the significant number of students in Anglophone West Africa and South Africa can be traced to histories of US missionaries who forged connections with Africans and facilitated the migration of students from the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth.

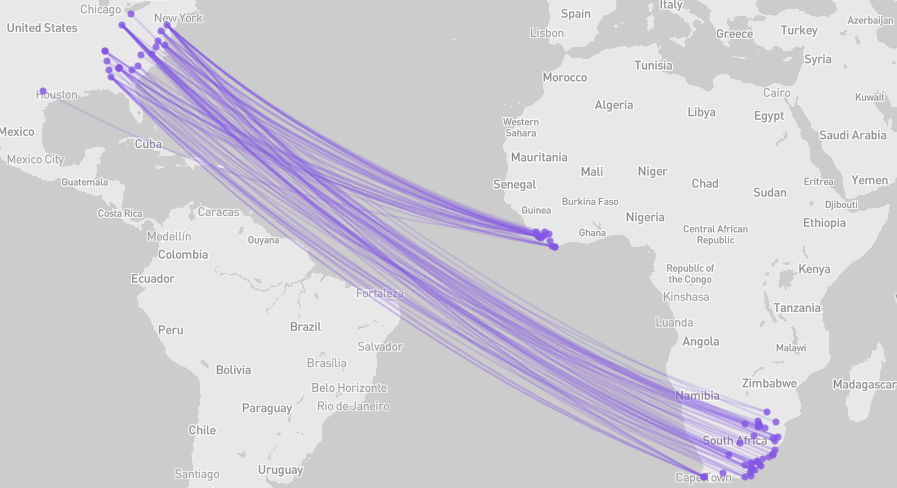

Figure 8. Liberian and South African Student Migration before World War II.Generated by the author using Palladio.

The early influence of Presbyterian missionaries in Liberia, Baptist missionaries in Nigeria, the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in South Africa, the United Brethren Church in Sierra Leone, and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Ghana partially accounts for the higher concentration of students hailing from these areas.18 Prior to World War II, African-American missionary connections to Africa played a significant role in facilitating the migration of students from Liberia and South Africa. The AME Church in particular, by conducting missions in South Africa during the late nineteenth century and early twentieth, is largely responsible for paving the way for South African students to attend schools like Wilberforce University in Ohio and the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Alabama during this period.19 In future versions of my mapping project, I hope to add a layer to the map that displays the presence of US missions in Africa to further tease out these religious connections.

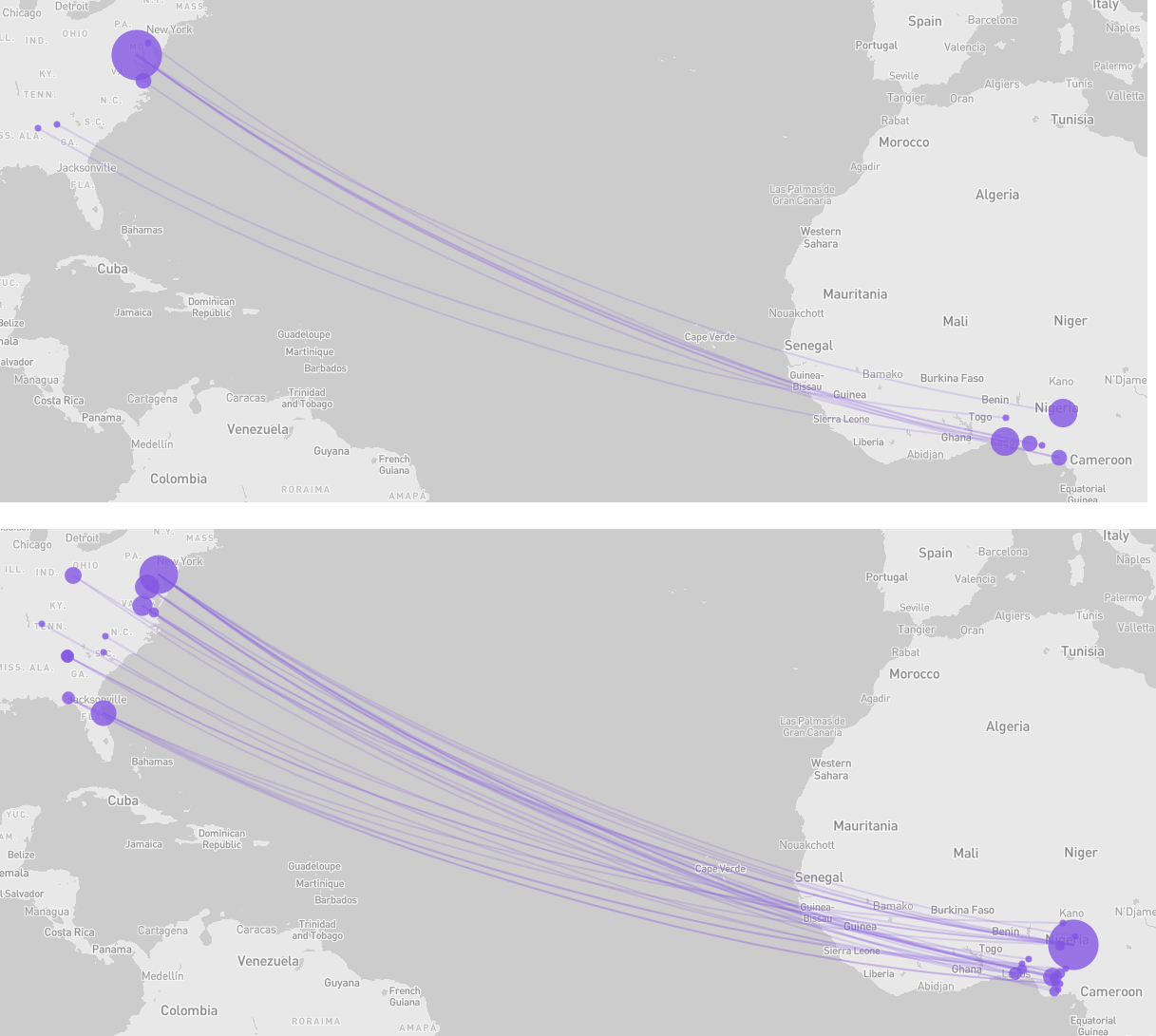

Figure 9. Nigerian student migration to HBCUs before (above) and after (below) Nnamdi Azikiwe’s return to Nigeria in 1937.Generated by the author using Palladio.

Yet missions were not the only animating force driving African student migration. Mapping African student migration to the US also allows us to visualize the impact that US-educated Africans had on fellow Africans back home. Nnamdi Azikiwe attended three HBCUs on his way to completing his undergraduate studies—Storer College in West Virginia, Howard University in D.C., and Lincoln University. During the decade before he began his studies at Lincoln, only thirteen Nigerian students attended HBCUs.

After graduate work at the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia University, Azikiwe returned to Nigeria in 1934. By 1939, as part of his activism in support of decolonization, Azikiwe sponsored a group of Nigerian men in their pursuit of education in the US so that they too could return home and contribute to decolonization efforts. Referring to themselves as “the Argonauts,” the group of students included Kingsley Mbadiwe, his brother George Mbadiwe, Nwafor Orizu, and Mbonu Ojike.20 All of the men began their education at Azikiwe’s beloved Lincoln. Their presence at the school would inspire future generations of Nigerian students to look to the US for higher education. As can be seen in the maps above, the number of African students at HBCUs hailing from Nigeria more than quadrupled during the decade following Azikiwe’s return to his home country. Two cohorts attended Lincoln University, while another cohort migrated to D.C. to attend Howard University, in no small part due to the ongoing influence of Nigerian students like Azikiwe who studied in the US.

While the point-to-point trajectories on the map suggest linear movement from Africa to a single destination in the US, the migratory journeys of students were often far more complicated.

While mapping illuminated some things about African student migration to HBCUs, there were other factors influencing African student mobility that mapping obscures or makes more difficult to visualize. In the case of mapping African student mobility, additional work is needed to highlight aspects of students’ movements that the map fails to capture. For relative ease of viewing, these maps illustrate the first institution each student attended. As mentioned previously, students often attended more than one institution during their stay in the US. Thus, while the point-to-point trajectories on the map suggest linear movement from Africa to a single destination in the US, the migratory journeys of students were often far more complicated. Future iterations of this digital project might include creating an animated map that allows viewers to trace the movements of students who began their education at one institution and ended at another. An animated map could also more seamlessly present the option of viewing changes in African student mobility over time.

Bond’s “African student survey” is a treasure trove for transnational historians and others interested in the relationship between migration, education, and geopolitics. The index cards provide hundreds of names and fragments of biographical information that otherwise remain scattered through a “globally dispersed shadow archive.”21 The work of transcription, digitization, and mapping begins to answer some questions related to African migration during the twentieth century, while also underscoring the need for further research. The questions that emerge are particularly useful for additional work in the Black digital humanities as they challenge scholars to continue exploring how migration informs Black social and political realities. As this project continues to develop, I hope to make my work available so that others may be inspired to ask questions of the data which, if answered, Bond argued, “would unfold a rich chapter of American history.”22 Exploring the contours of African migration invites scholars to be flexible in their archival and research methods—to be as mobile as our subjects of study.

Bond began using index cards to organize his research materials after learning this method from a classmate during his time as a graduate student at the University of Chicago. Wayne J. Urban, Black Scholar: Horace Mann Bond, 1904–1972 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1992), 33. ↩︎

The dates correspond with when the student appears in college and university catalogs. Although Bond’s study focused on HBCUs, his data includes students from two Ohio institutions that are not categorized as HBCUs. Both Oberlin College and Otterbein University were two of the earliest non-HBCUs to welcome African-American and African students. ↩︎

James T. Campbell, Songs of Zion: The African Methodist Episcopal Church in the United States and South Africa (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1998), 250; Liping Bu, Making the World Like Us: Education, Cultural Expansion, and the American Century (Westport: Praeger, 2003); Manna Duah, “‘The Right Kind of Africans’: US International Education, Western Liberalism, and the Cold War in Africa” (PhD diss., Temple University, 2020); Paul A. Kramer, “Is the World Our Campus? International Students and US Global Power in the Long Twentieth Century,” Diplomatic History 33, no. 5 (November 2009): 775–806, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44214049. Matthew K. Shannon, Losing Hearts and Minds: American-Iranian Relations and International Education during the Cold War (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017). ↩︎

“First and Highly Tentative Draft of an Outline for a Research and Action Program by the United Negro Colleges on ‘The African Student in the United States,’” September 1959, African Students Survey: General, January 15, 1959–June 11, 1960, Horace Mann Bond Papers, MS 411, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives, UMass Amherst Libraries (hereafter cited as HMBP). ↩︎

Processing the text using text recognition software was especially challenging because at least two kinds of handwritten script were used on the cards and certain categories of data (for example, the student’s area of study) were not available on all of the cards. ↩︎

See, for example, Sylvia M. Jacobs, “James Emman Kwegyir Aggrey: An African Intellectual in the United States,” Journal of Negro History 81, no. 1/4 (Winter–Autumn, 1996): 47–61, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2717607; Kenneth J. King, Pan-Africanism and Education: A Study of Race, Philanthropy and Education in the United States of America and East Africa (Brooklyn: Diasporic Africa Press, 2016); Anton Tarradellas, “Pan-African Networks, Cold War Politics, and Postcolonial Opportunities: The African Scholarship Program of American Universities, 1961–75,” Journal of African History 63, no. 1 (March 2022): 75–90, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853722000251. ↩︎

Cortlandt Van Rensselaer, God Glorified by Africa: An Address Delivered on December 31, 1856, at the Opening of the Ashmun Institute, Near Oxford, Pennsylvania (J.M. Wilson, 1859), 41–43. ↩︎

Outline for “A Proposed Research and Action Program by the United Negro Colleges on the Subject: ‘The African Student in the United States,’” African Students Survey: General, January 15, 1959–June 11, 1960, HMBP. ↩︎

Horace Mann Bond, Education for Freedom: A History of Lincoln University, Pennsylvania (Lincoln University, PA: Lincoln University, 1976). ↩︎

Kim Gallon, “Making a Case for the Black Digital Humanities,” in Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016, ed. Lauren F. Klein and Matthew K. Gold (Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 2016), 44, https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctt1cn6thb.7. ↩︎

Dan Edelstein et al., “Historical Research in a Digital Age: Reflections from the Mapping the Republic of Letters Project,” American Historical Review 122, no. 2 (April 2017): 409, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26576710. ↩︎

See, for example, Jacob K. Olupona and Regina Gemignani, eds., African Immigrant Religions in America (New York: New York University Press, 2007). ↩︎

Anton Tarradellas and Romain Landmeters, “Les Mobilités des étudiantes et des étudiants africains: une histoire transnationale de l’Afrique depuis la décolonisation,” Diasporas. Circulations, migrations, histoire, no. 37 (February 2021): 3, https://doi.org/10.4000/diasporas.6089. ↩︎

Fatima Massaquoi, The Autobiography of an African Princess, ed. Vivian Seton, Konrad Tuchscherer, and Arthur Abraham (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). ↩︎

“The Immigrant Army: Immigrant Service Members in World War I,” US Citizenship and Immigration Services, last modified March 5, 2020, https://www.uscis.gov/about-us/our-history/stories-from-the-archives/the-immigrant-army-immigrant-service-members-in-world-war-i. ↩︎

Jacobs, “James Emman Kwegyir Aggrey.” ↩︎

See, for example, Obed Mfum-Mensah, Education Marginalization in Sub-Saharan Africa: Policies, Politics, and Marginality (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2018). ↩︎

See Campbell, Songs of Zion for a discussion of the AME Church and South African students at Wilberforce University. Campbell, 249-94. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Gloria Chuku, “Mbonu Ojike: An African Nationalist and Pan-Africanist,” in The Igbo Intellectual Tradition: Creative Conflict in African and African Diasporic Thought, ed. Chuku (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). ↩︎

Jean Allman, “Phantoms of the Archive: Kwame Nkrumah, a Nazi Pilot Named Hanna, and the Contingencies of Postcolonial History-Writing,” American Historical Review 118, no. 1 (February 2013): 129, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23425461. ↩︎

“First and Highly Tentative Draft of an Outline,” HMBP. ↩︎