PROCESSES

Mapping Persian Literacy in Early Modern South Asia

On May 15, 1722, in the town of Gujranwala, Sayyid ʿInayatullah produced a manuscript: a commentary on one of the most well-read books in human history, the Gulistan of Saʿdi. Before discussing the significance of the Gulistan and its commentaries, we might well ask: What’s special about a manuscript?

Imagine a historian two hundred years from now who wants to write a history of our times. She could access a range of sources: government documents, digital archives, social media feeds of dead people, the books and newspapers that we produced, the statues we erected, and so on. For a historian who wants to write a history of an era before print, however, sources are considerably limited. The problem is further exacerbated for a region like South Asia, where two centuries of British colonialism systematically distorted local libraries, archives, and collective memory. The sources that can shed light on India’s past are accordingly fewer in quantity and scope than, say, sources on France or England. In this context, manuscripts produced in India acquire immense value as both carriers of textual knowledge and material artifacts of the past.

What gender and sexual norms were everyday Indians being socialized in? How did they conceive of sexual desires, identities, and acts?

Generations of Indian historians, of course, have recognized the importance of manuscripts. Working on such diverse themes as politics and economy, gender and sexuality, scholars have drawn on these texts to illustrate some features of India’s past. These sketches are incomplete, however, not only due to the paucity of sources, but also because every source carries a particular perspective to the exclusion of others. For instance, we know much more about Indian elites than the Indian laity because the most well-preserved manuscripts are those produced at the imperial court at the behest of rich, royal patrons. They formed the core of royal libraries, many of which were looted by the British and other European collectors and transported to Europe. For social and cultural historians, an overwhelming focus on these sources has meant that our present knowledge about everyday Indians distant from the court remains rather limited. This is especially the case for histories of gender and sexuality in early modern India, the era roughly between 1600–1850. What gender and sexual norms were everyday Indians being socialized in? How did they conceive of sexual desires, identities, and acts? Manuscripts of the Gulistan can provide important clues.

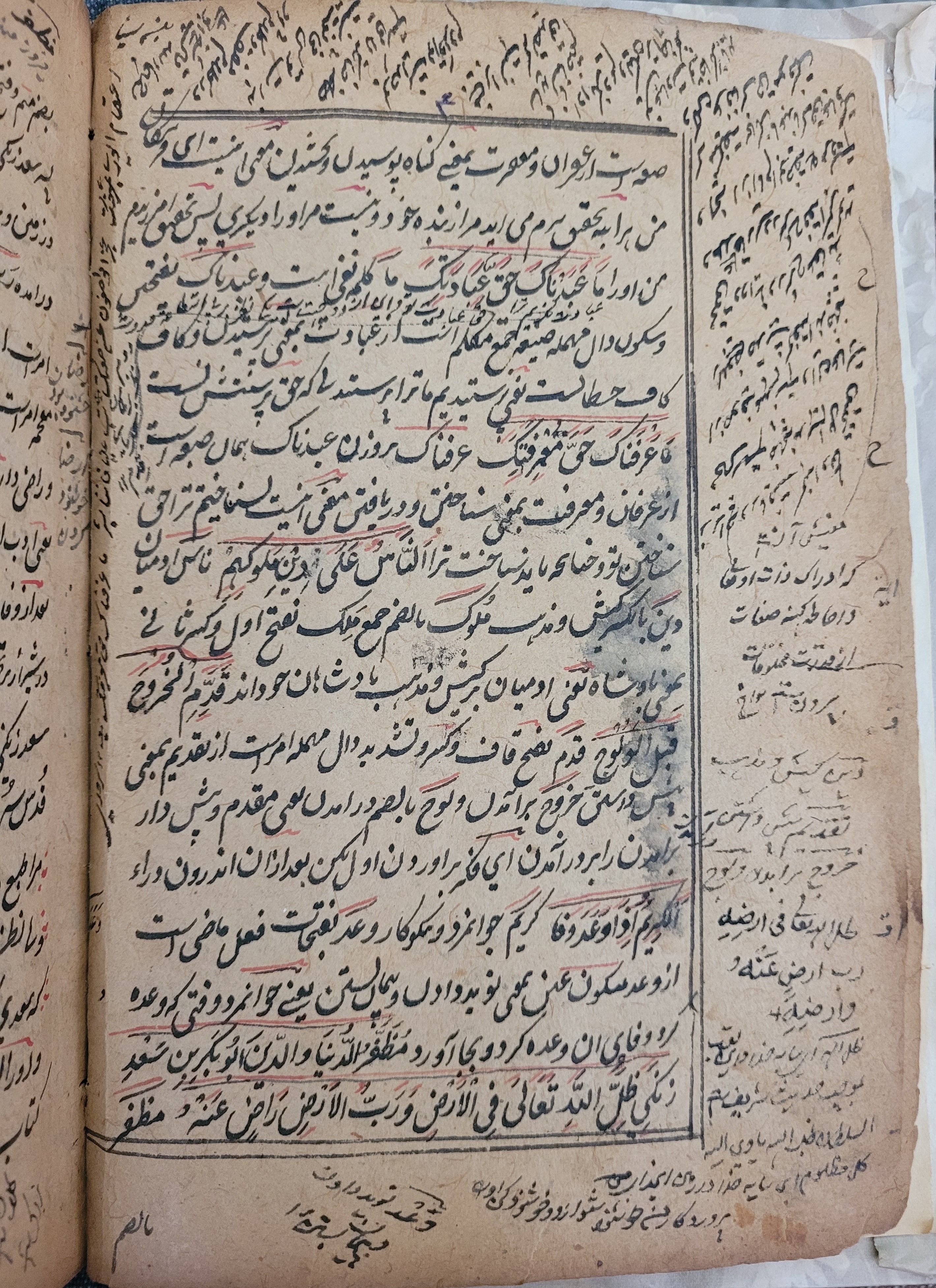

Figure 1. Page from ʿAbdul Rasul bin Shihab al-Din Qurashi, “Sharḥ-i Gulistān-i Sa’dī,” 8919, fols. 1–2.Ganj Bakhsh Library, Iran-Pakistan Institute of Persian Studies, Islamabad, Pakistan.

The Gulistan (Rose-Garden) was composed in the mid-thirteenth century by the famous Persian writer and poet, Shaykh Saʿdi (d. 1291 CE). Composed in Shiraz, part of present-day Iran, copies of the Gulistan soon found their way to India. The book became so popular that it was made a part of school curricula and became the subject of scholarly commentaries. Today, historians agree that the Gulistan was used as a textbook for inculcating Islamic ethics and the Persian language. To get a later, seventeenth-century view of its importance, let us read the words of one commentator. Writing shortly after 1662 CE (1073 in the Hijri calendar),1 ʿAbd al-Rasul Qurashi noted that the Gulistan includes “sweet poetry and colorful prose” and that “all its exhortations are aligned with the knowledge of practical philosophy (hikmat-i ʿamali) and all its lessons with the science of ethics (ʿilm-i akhlaq).” Unfortunately, students were unable to fully benefit from the text because

[t]he handling by children and the slippages of their tongues and the corrections of lowly, ill-qualified instructors and those of the unbalanced, weak-spirited schoolmasters (maktab-dāran)—those who have not acquired the central meanings of the text—have made certain inappropriate [passages] part of the poetry and erased some appropriate passages. This has led to the brilliant textual features (ʿibārāt-i rāyiʿah) and the high implications (ishārāt-i fāyiqah) of the Gulistan to be distorted.2

As this passage indicates, the Gulistan was being taught in the classrooms of early modern India. In fact, it was a mandatory component of a transregional curriculum followed not just in India but also in Central Asia, Iran, and the Ottoman Empire. The goal of this curriculum was to inculcate adab, a term that refers both to the proper use of language (exemplified in literary works) and to refined social behavior.3 As a text of adab par excellence, the Gulistan taught students how to behave and how to use and appreciate language. Not all teachers were adequately trained to teach the text, however, which is why commentators sought to clarify the ethical lessons and the linguistic beauties of the text.

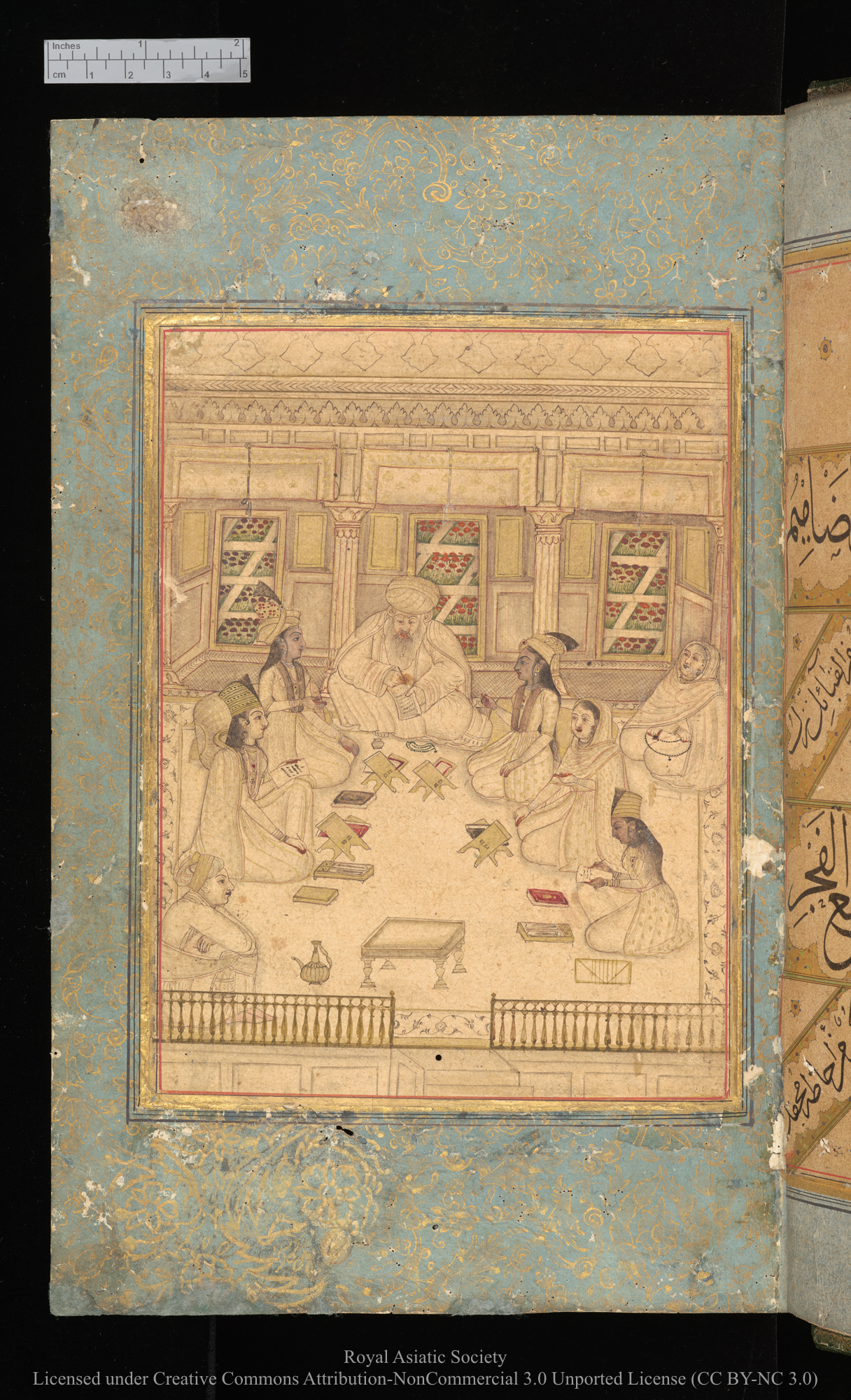

Figure 2. An elderly man teaching female students and attendants. The illustration is inserted (probably at a later date) into a Gulistan manuscript copied at Fatehpur Sikri in 990 HJ / 1582-3 CE. Collection of the Royal Asiatic Society, RAS Persian 258. (accessed October 2, 2024). Figure 2. An elderly man teaching female students and attendants. The illustration is inserted (probably at a later date) into a Gulistan manuscript copied at Fatehpur Sikri in 990 HJ / 1582-3 CE. Collection of the Royal Asiatic Society, RAS Persian 258. (accessed October 2, 2024). The online version of this essay includes an interactive deep zoom viewer displaying a high resolution version of this image.

Who were the different groups of students studying the Gulistan? Given the central importance of the text to the cultivation of Muslim ethics, the Gulistan was studied by royal princes and princesses, as indicated in the portrait above in one of the most finely-illustrated manuscripts of the Gulistan produced at the royal court. But much has already been written about the Mughals’ patronage of Persian literature. In fact, there is a longstanding assumption that Persian was primarily a language of the Mughal elite and was cultivated mostly in urban centers close to imperial and regional courts.4 But we know that the Gulistan was widely used as a text for schoolchildren. If we can find further evidence that manuscripts of the text and its commentaries were produced in regions far away from imperial courts, we will begin to see that Persian literature was much more broadly cultivated in early modern India. My ongoing project at The Center for Digital Humanities at Princeton University presents some of this evidence.

The map above plots some of the manuscripts of the Gulistan and its commentaries that were produced in India between roughly 1650–1900. The raw data for the map was derived from the bibliophilic labor of Ahmed Monzavi, a cataloger from Iran who, together with a team of researchers, undertook a massive research project spanning the late 1950s to the early 1980s. Monzavi and his team cataloged all the Persian manuscripts then present in the libraries of Pakistan. This team of scholars browsed through manuscripts scattered across the country, whether in small village libraries, special collections in universities, or the private collections of individuals. The output of this labor of love is a fourteen-volume tome, an extract of which was printed separately: manuscripts of the writings of Saʿdi.5 In this small book are listed about 370 manuscripts of the Gulistan itself and about two hundred manuscripts of commentaries on the text. These are the manuscripts that found their way into a recognized collection in Pakistan. There were probably thousands of additional manuscripts produced in South Asia. Some of these are located in libraries in India; many were taken to other parts of the world. Princeton University, for instance, holds a manuscript of a Gulistan commentary that was composed in Dehvi, a village in the mountainous state of Himachal Pradesh in Northern India. A large number of manuscripts, however, was destroyed over time by human negligence and such elements as wind, water, and worms.

The manuscripts cataloged in Monzavi’s book are therefore only a fraction of the actual number of Gulistan manuscripts and commentaries that circulated in early modern India. When it comes to identifying the places of origin of these manuscripts, we encounter obstacles that further limit our already delimited data set. For example, many entries do not include a place of origin at all. This means that the cataloger could not identify an explicit place where the manuscript was first copied using the front matter or end matter, the handful of pages that a cataloger usually scans when compiling a manuscript’s meta-data. (There could, nonetheless, be other clues to the place of origin in the manuscript that await discovery by future scholars who read the manuscript in its entirety.) Even when a location is given, the exact provenance can be ambiguous. We are told, for instance, that one commentary was copied on June 22, 1890 CE, in Sharifabad. But, in early modern times and even today, there were many towns referred to by the name of “Sharifabad.” Because this manuscript is currently located in a library in Sargodha near Okara, Punjab—just over a hundred miles from one of these Sharifabads—we can assume that’s where it was created. But this goes to show the degree of detective work that is needed to place these manuscripts accurately.

The existence of a single manuscript reveals an entire world of knowledge production and transmission in this small village of Hesarak.

Applying similar methods, we can also gain strong indications—if not definitive information—about the place of origin using the name of the scribe. In India, it has been common practice (even until the early twentieth century) to share one’s hometown when giving one’s name. For instance, on July 6, 1846, a Gulistan commentary was copied by “Muhammad Hasan mutawattin-i Bhagiyan,” which means “Muhammad Hasan whose watan (home) is/has become Bhagiyan” (Bhagiyan is a village in Northern Punjab). In such cases, we can be almost certain that the manuscript was produced in Bhagiyan. However, in some cases, the scribe does not tell us where he is currently based, but follows another common practice of the time by giving a place moniker. For instance, one manuscript was copied by an “Abu al-Fatḥ Sialkoti.” Sialkoti is the adjectival form of Sialkot, a city in Pakistan that has acquired global fame for its sporting goods.6 It is highly probable that the scribe was in Sialkot at the time he produced the manuscript, but it is also possible that he might have moved to a different city yet retained the moniker “Sialkot.”

Such are the ambiguities and approximations that inevitably attach to writing about the past. Far from making historiography a futile enterprise, the gaps in our knowledge can provide opportunities for further inquiry. A future historian, for instance, might uncover a vibrant culture of Persian-language study in early modern Sialkot, supporting the idea that the manuscript was produced there. One could travel to the library where the manuscript is now held and check its records for the source of the manuscript—perhaps it was donated by a private collector whose descendants can shed some light on the manuscript.

Historians can also increase the accuracy of their claims by collating their data together. That is, while I might not be one-hundred-percent certain about an individual manuscript, a claim based on a group of manuscripts would hold greater confidence. I turn, therefore, to some of the striking patterns that emerge from the data, in addition to some individual peculiarities.

On May 24, 1877, Muhammad Sharif “Nangarhari” inscribed a Gulistan commentary in Hisarak, a village in Nangarhar province in Western Afghanistan (the westernmost pin on our map). Its population in 2002 was estimated to be just thirty thousand. The fact that a Gulistan commentary was copied there implies a few facts about this village in the nineteenth century: that there was at least one professionally trained scribe (Muhammad Sharif) who could copy Persian books; that there was at least one other manuscript of the same commentary from which Sharif produced his copy; that there were copies of the Gulistan, for the teaching of which someone felt the need to have a copy of a commentary; that there was a patron who could pay for the production of the copy; that there were parchment and ink with which the copy could be produced. In other words, the existence of a single manuscript reveals an entire world of knowledge production and transmission in this small village of Hesarak. The fact that our map features a number of such small towns and villages suggests a remarkable reach of Persian literacy beyond courtly elites.

The content of the Gulistan and its commentaries can also shed broader light on medieval Indian culture and society. Some stories in the book talk about a man’s attraction to a male youth on account of the rosy down on his cheeks; others mention the power of female sexual desire in ways that so shocked European readers of the nineteenth century that they censored these stories altogether from their English translations. One frequently omitted story goes thus:

An old man was asked, “Why don’t you take a wife?”

“I don’t take any pleasure in old women,” he replied.

“Get a young one,’ they said, “since you are rich enough.”

“Inasmuch as I, who am old, have no inclination for old women, what love could a young woman have for me?”

[verse] Potency is necessary, not gold / a woman prefers a hard carrot to ten maunds of meat.7

How did early modern readers engage with such stories? Did they find them unsuitable to be included in a textbook of Islam, as many modern Muslims undoubtedly feel? The commentaries on the Gulistan here provide clues. We see that the commentators, unlike later European and Muslim readers, far from displaying any consternation or criticism of such passages, found it important to explicate the passages so that Saʿdi’s message is clear. In this case, for instance, the commentators clarified the anatomical reference in the verse. In fact, many commentators stressed the importance of a wife’s sexual satisfaction to a healthy marriage. My ongoing dissertation research delves further into the content of the commentaries, especially how the commentators interpret stories pertaining to same-sex desire in ways that disrupt contemporary understandings of the links between desire and selfhood. Here, my point is just to indicate the ways in which tracing the circulation of Gulistan manuscripts can shed light on wider historiographical questions.

Among these wider questions are those of Hindu-Muslim relations and the extent to which cultural and social norms were shared amongst them. The Gulistan manuscripts provide evidence that the world of Islamic ethics was not restricted to Muslims. For example, on April 6, 1701, Nanakchand, a Hindu scribe, copied a Gulistan commentary for a Hindu patron named Nisbat Raʾye (the commentary is now in a library in the small town of Bhalwal in central Punjab). As further evidence of the participation of other religious groups in the world of the Gulistan, we find some manuscripts in Monzavi’s catalog which—as opposed to the majority of entries that use the Islamic Hijri calendar—give the date in the Bikrami calendar that was followed by the Sikh and Hindu communities in the Punjab. These facts are direct evidence that some non-Muslims also patronized Perso-Islamic texts, while others were sufficiently trained in Persian to serve as professional scribes. While it is well established among historians of medieval India that peoples of different faiths served in the Mughal bureaucracy, direct evidence of non-Muslims’ participation in the Persian scholarly milieu away from imperial and regional courts is significant.

Beyond these generic patterns, the visual representation of the data draws our eyes to particularly interesting points. The concentration of points in and around the Lahore region in the Punjab probably reflects the fact that the two largest collections of Persian manuscripts in Pakistan are held by the Punjab University in Lahore and the Ganj Baksh Library in Rawalpindi. But the spread is also illustrative. For instance, a manuscript now in Karachi has traveled all the way from Solapur in Southern India. Not coincidentally, this manuscript is in the naskh script, as opposed to the nastaʿliq script that was more common in Northern India. One manuscript, dated to around the 1800s, was produced in a town in Bihar and is currently located in Peshawar. Within a couple of centuries, it has traveled thousands of miles. How, why, and by whom did this movement take place? These are questions that might make for a riveting historical drama, and one hopes that future researchers can pursue them.

Figure 5. The Mohabbat Khan Mosque, located in Peshawar, Pakistan.Wikimedia Commons

This brief article has attempted to give a sort of extended caption to an interactive map of Gulistan manuscripts produced in early modern India. Though recognizing all the limitations of the project, I have followed an Arabic proverb often cited by the authors of commentaries: “Whoever cannot encapsulate all, should not leave all.” I hope that it can inspire me and others to explore the understudied world of Perso-Islamic manuscripts in India.8

Acknowledgments

I extend my gratitude to a number of people: Maulana Dr. Sabeeh Hamdani, for his help in deciphering the commentaries; Muhammad Siddique Anjum, for helping me extract data from the catalogs and plotting it onto Excel; Arif Noushahi Sahib, for helping me identify obscure places; Wouter Haverals, for revealing the wonders of Leaflet; and Grant Wythoff, for his consistent encouragement and support from the very start of the project through to its present stage. I am also grateful to other fellows and staff at The Center for Digital Humanities at Princeton University, and to many friends and advisers who will be recognized properly in my dissertation acknowledgements. I remain perpetually indebted to Aysha Saeed Hameed, my wife, whose love and care keep me going.

Before the coming of European colonialism, the main calendar used across the Muslim world from Spain to Southeast Asia was the Hijri calendar. It is based on the lunar cycle, which means that a year given in the Hijri calendar can correspond to two years of the CE calendar. For instance, the year 1446 Hijri will span parts of 2024 and 2025 of the CE calendar. ↩︎

ʿAbdul Rasul bin Shihab al-Din Qurashi, “Sharḥ-i Gulistān-i Sa’dī,” 8919, fols. 1–2, Ganj Baksh, Rawalpindi. All translations in this article are my own, unless otherwise noted. ↩︎

For an excellent article on adab and the transregional curriculum that fostered it, with special reference to the Gulistan, see Mana Kia, “Adab as Ethics of Literary Form and Social Conduct: Reading the Gulistan in Late Mughal India,” in No Tapping Around Philology: A Festschrift in Honor of Wheeler McIntosh Thackston Jr.’s 70th Birthday, eds. Alireza Korangy and Daniel J. Sheffield (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2014), 281–308. ↩︎

A good illustration of this view comes from Francis Robinson, for whom “Perso-Islamic culture,” as he puts it, was decidedly elite. It was the culture of the Muslim ashraf [“the respected”] who came from outside India. These outsiders were mainly “town-dwellers” in towns that were “islands of international Perso-Islamic civilization set in countrysides dominated by local cultures, some barely Islamic, others not Islamic at all.” Francis Robinson, The ‘Ulama of Farangi Mahall and Islamic Culture in South Asia (London: Hurst , 2012). ↩︎

Ahmed Monzavi, Sa’di Through the Manuscripts of Pakistan (Iran-Pakistan Institute of Persian Studies, 1985). ↩︎

Naeem Abbas, “‘Made-in-Sialkot’ Adidas Ball Puts Pakistan in the World Cup,” Reuters, December 9, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/sports/made-in-sialkot-adidas-ball-puts-pakistan-world-cup-2022-12-09/. ↩︎

With slight modifications, this translation is taken from Wheeler M. Thackston, The Gulistan (Rose Garden) of Sa’di (Bethesda: Ibex Publishers, 2008), 129. ↩︎

As this piece was going through the final proofs, I discovered “The Persian Tadhkira Project” which maps tadhkiras (biographical anthologies) of Persian poets produced and circulating across the Persianate world, c. 1200-1900. For more, see Kevin L. Schwartz, “A Transregional Persianate Library: The Production and Circulation of tadhkiras of Persian Poets in the 18th and 19th Centuries,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 52.1 (2020): pp. 109-135. ↩︎