Scribes

Serendipity in the Cairo Geniza

Matthew Dudley is a PhD candidate at Yale University where he is completing a dissertation on the early modern Cairo Geniza of the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries. Steffy Reader, a retired psychotherapist, has contributed to the Scribes of the Cairo Geniza and a number of other Zooniverse projects since 2018. In the clip below, they meet for the first time during the conference Crowdsourcing and the Humanities and discover that they had already been collaborating anonymously via the Scribes of the Cairo Geniza site. What follows is a dialogue between them about this moment and the results of their serendipitous collaboration in analyzing communal register fragments from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Matthew: In this piece Steffy and I continue the conversation from our April 2021 panel in order to explain the basis of our collaboration, the processes by which we analyze Geniza texts and, most importantly, the stakes of crowdsourcing projects for historical research. Steffy’s work in compiling collections of Geniza fragments with similar formatting, scribal hands, and ink stamps alerted me to the existence of document types that could have otherwise taken months or years to locate. Her individual contributions speak volumes for the ways in which a vast network of Scribes contributors has accelerated the accessibility of Geniza texts. Contributors like Steffy are tackling foundational questions in the field of Cairo Geniza Studies that have never been pursued on such a mass scale. From the moment I happened upon the Scribes discussion boards in the summer of 2020, I was struck by the abundance of user collections and comments regarding the distinctions between genres of literary and documentary fragments.1 Steffy, in your volunteer work and collections, what are the core features within the layout of texts that you focus on in order to distinguish between fragment types?

Steffy: Since I can’t read Arabic or Hebrew, I take skilled handwriting in straight lines with justified margins as signs of the work of professional scribes. Many, but not all, literary texts are neatly written by professional scribes using “square” Hebrew letters, with strictly justified margins. Liturgical poetry, for example, whether written by a scribe or not, might have an unjustified left margin, with a pattern of longer and shorter lines, like poetry in English, but read from right to left. Careful layout, good margins, and straight lines of beautiful script indicate to me that a fragment is “literary,” but other literary fragments (sermons, for example) may lack these features. I’m often unsure what type of fragment I’m looking at, so I like to read the notes on a fragment from the library that holds it, and any comments at the Scribes of the Cairo Geniza site. This slows my volunteer work, but greatly enriches my experience.

The documentary texts are widely varied. Many legal documents, for example, look like the work of professional scribes. Letters from one merchant to another, some with margins crammed full of text written at an angle to the main text, look urgent rather than orderly. Still others are scrawled on re-used scraps of paper in handwriting that is far from well trained. That was true of the “communal register” which you mentioned during our panel last April. In those fragments, a less skilled writer kept dated weekly records that always included some simple math sums. What might these fragments be?

Matthew: Just as you have noted, Steffy, besides the layout of texts and the economical usage of paper, some other features for assessing the genre of Geniza fragments lie in script usage and the distribution of numerical figures. Square Hebrew letters, or “ מרובע / merūbaʿ,” are indeed a helpful indicator for tracing sacred literary texts. In the period I work on, between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, many Geniza texts begin to bear the influence of Sephardi rashi and solitreo scripts. As a result of the immigration of Sephardi refugees into Egypt across the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries—but especially after the Spanish expulsion of the 1492 CE—Geniza fragments portray the increased influence of Iberian systems of Hebrew script.2

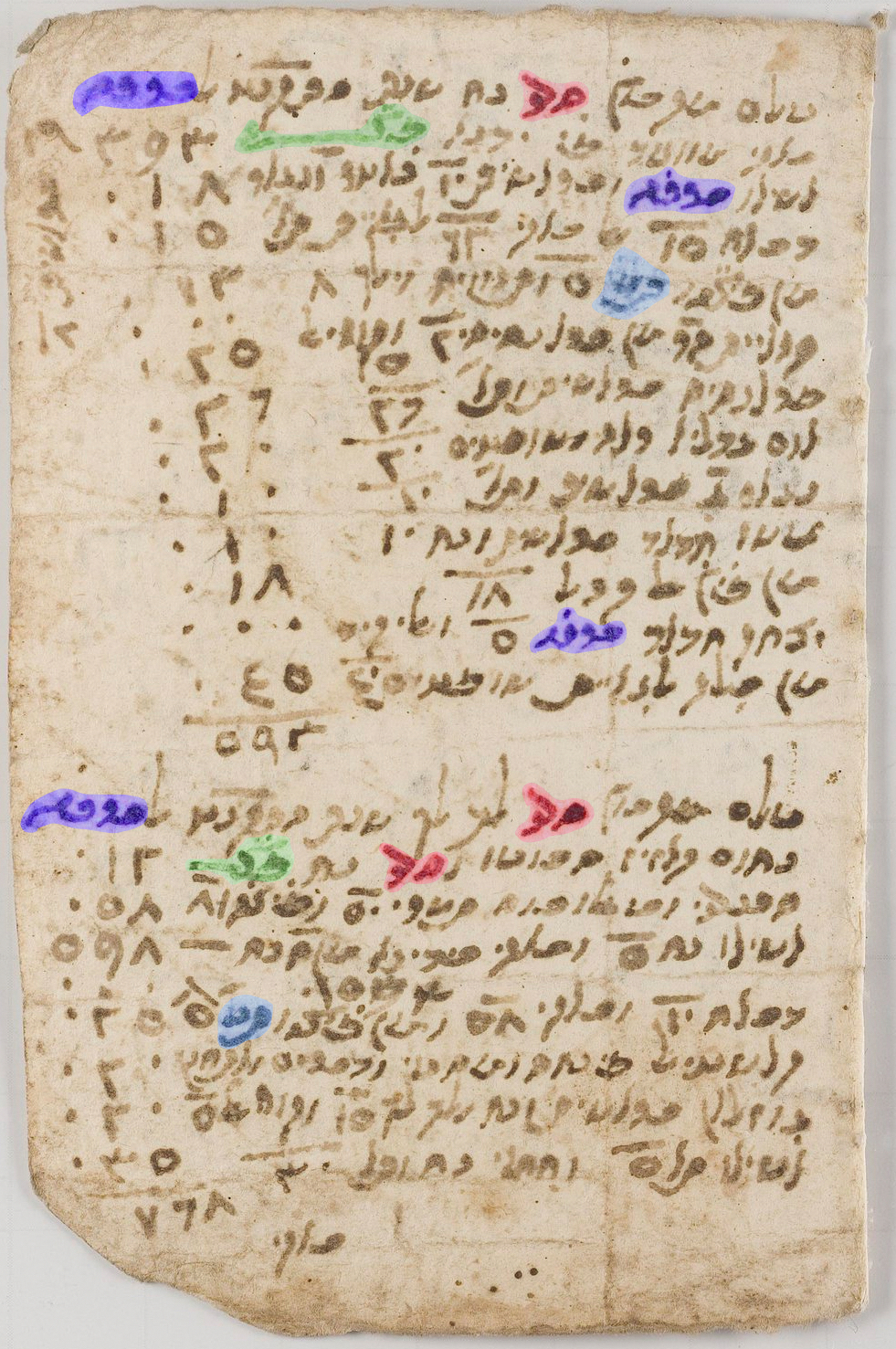

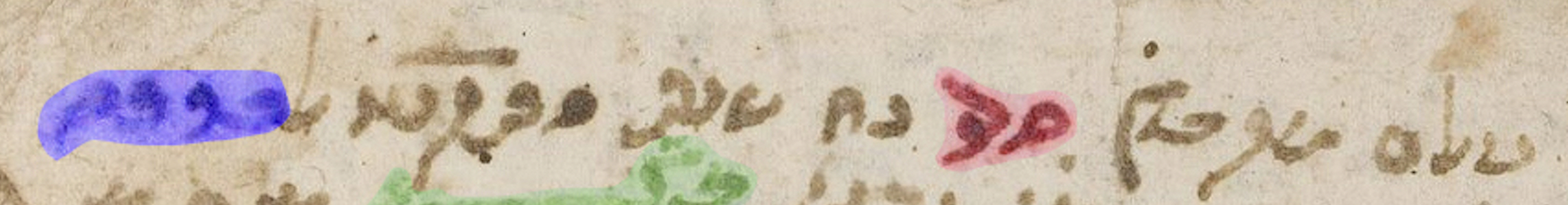

Studying solitreo letter forms—which were more commonly used in writing Judeo-Spanish—can also be helpful for understanding how a variety of documents from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries incorporate cursive writing. So, for example, in the Judeo-Arabic communal register I referenced during our panel, on occasion, there are interconnected letters in repeating words such as “berakha / blessing / ברכה” (in purple), “fiḍḍa / silver / פצה” (in green), and “seder / order / סדר” (in red).3 These cursive forms give the initial impression of messiness and lack of scribal skill yet it’s crucial to recognize the pragmatic significance of this writing method. Connecting letters and abbreviating Judeo-Arabic words such as “ת׳׳ע / t[asāwī] ʿa[la]” (in blue) increased the speed at which a scribe could record notes when calligraphic aesthetics were not the objective.4

Image 1. Subject 12499256 (ENA 624.22, Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary): Color-coded annotations of solitreo cursive letter forms and abbreviations, October 1798 CE.Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary

The headings of this fragment from Steffy’s collection5 were recorded during the weeks of October 7–20 1798 CE–just before the Revolt of Cairo unfolded on October 21–22nd when the city’s residents fought to eject the French occupation under the leadership of Napoleon Bonaparte. The Jewish calendar dating appears in the heading of each list and it follows a shared formula throughout this type of communal register:6

Image 1.2. Translation of the Upper Heading in Subject 12499256 (ENA 624.22) “עלם מקבוץ סדר נח שנת התקנט לברכה” “Account from [the] collection [during the week] of the seder Noaḥ [biblical reading in] the year 5559, may it be a blessing”

The surnames mentioned in each list–such as Vialobos, Ḥadād, and Skenderī –embody the lives of individuals and families who experienced one of the most turbulent periods in Egyptian political history. Between 1798–1801 CE, the Egyptian populace withstood immense hardship in their efforts to defeat the French occupation and then between 1801–1805 as Ottoman military factions fought to assert their control over the province (a process which resulted in Muḥammad ʿAlī’s rise to power as Pasha/Governor). What makes these register entries so significant, then, is that they offer a continuous internal perspective on how Cairene Jews supported their communal institutions during a period of harrowing instability.7 In my dissertation, I am working to compile the donation data from the many page fragments of these registers. This line of investigation may have never emerged in my research had it not been for my chance encounter with Steffy’s collection in the Scribes database.

Steffy: Shortly after I began volunteering in early 2018, a batch of these oddly similar fragment images started to pop up. Volunteers could tell these Hebrew script fragments were the work of a single less skilled writer but not why he had written so many similar-looking notes. They did not look like religious texts, legal documents, or letters.

A basic task for the “citizen humanists” who volunteer in the Scribes of the Cairo Geniza project is to try to sort images of the fragments which accumulated in the Geniza for nearly a thousand years into two piles: those in Hebrew script, and those which display some Arabic script. Even for volunteers who, like me, cannot read these scripts, this is usually easy to do.

As I wondered what these fragments were, I realized that each one had areas which showed math sums done in Eastern Arabic numerals.8 Perhaps these fragments were entries in a ledger recording an activity which might interest an historian someday?

I had just begun keeping a list on paper of these fragments when one with an Arabic seal (a rare feature which volunteers are asked to report) and large, beautiful Arabic writing on one side appeared on my computer screen. Startled, I decided to make a digital collection of these fragments, hoping that they might be useful to someone’s scholarly research.

But I never imagined that I would meet that person.

Meanwhile, as more and more of these fragments turned up and added to my collection, Scribes project researchers Jasmin Shinohara and Professor Marina Rustow provided information about the dates and partial translation of the text of the fragments.9 I am very grateful to them both for that information, and for giving time and attention to the curiosity of a new volunteer at Scribes who wondered what she was looking at.

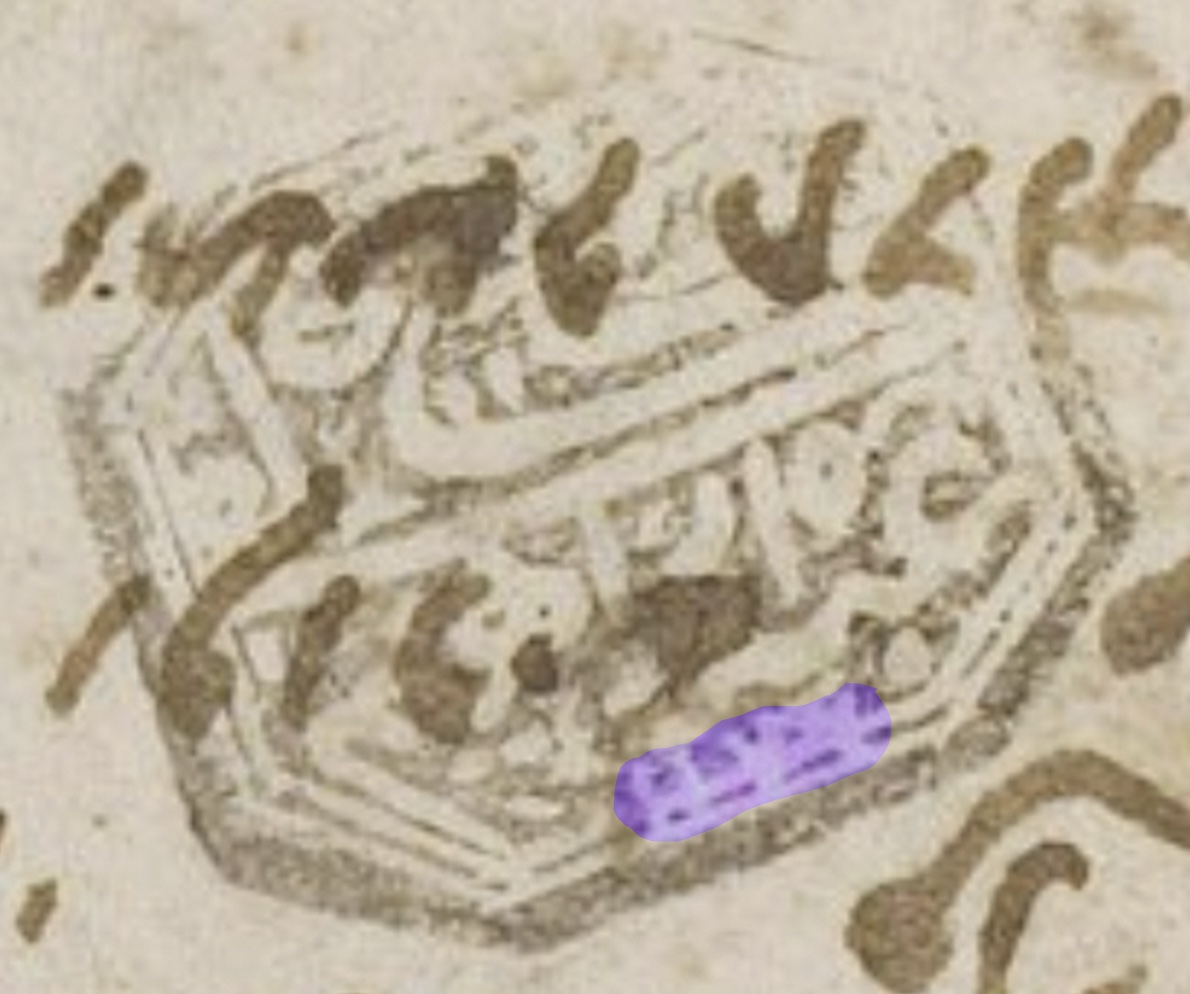

Matthew: Likewise, when I mentioned the Scribes user “Citsci-Rancho’’ during our panel discussion I had hoped they might be watching the panel or eventually see the recording. The serendipity of being able to collaborate on and to answer these questions is a rare opportunity. The seal you included in the register collection is crucial for two reasons. Its significance lies, firstly, in the dating– where the Hijrī year ١١٧٧/1177 AH or 1763/64 CE is visible (in purple):10

Image 2. Subject 12499254 (ENA 624.20, Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary) Ink stamp on recycled paper includes Hijrī year ١١٧٧/1177AH.

When we read the Hijrī year 1177 AH on the recycled paper against the dating of the upper layer of usage (September 29–October 5, 1799)– a difference of roughly 35 years emerges.11 This timespan marks the initial lifecycle of a piece of paper that lost its utility but was later cut up and bound within a communal register. As Rustow has shown with medieval Geniza sources, early modern ones too can help us analyze the periodicity of paper recycling in Egypt.12

The other point of significance with this seal is that the register entries recorded over it reference a specific congregation and synagogue in Cairo: “ק׳׳ק תורקייה / K[ehillat] K[odesh] Tūrkīya.”13 This connection is critical because it frames one of the communal settings in which these sources were recorded. When we collect in-text locational references, our opportunities multiply for studying the lives of individuals: more specifically, in tracing their donorship activities and congregational membership.

Steffy’s and my own initial encounters with these fragments have yielded a chain of shared findings that ties back into a broader web of individual contributions in the Scribes database. The initial results of this network of collaboration and those on the horizon underscore the stakes of crowdsourcing in historical research. Moreover, our findings capture the continued resonance of Solomon Schechter’s words when he stated:

“The Geniza is a world, with all its religious and secular aspirations, longings and disappointments, and it requires a world to interpret a world, or at least a large staff of workers.”14

Jessica L. Goldberg and Eve Krakowski offer a helpful overview of the distinctions between literary and documentary fragments: “forms of geniza practice varied not only among communities but also over time, with some periods during which the Ben Ezra Geniza was in use seeing significant deposits of non-sacred material. Most of the Geniza papers–about 380,000 folio pages in all–are fragments of literary manuscripts, largely on religious subjects. But somewhere between thirty and fifty thousand fragments are what is usually termed documentary material; that is, they are everyday writings, texts written not to convey ideas to an anonymous and long-lasting audience but to communicate with specific recipients for immediate practical purposes.” Jessica L. Goldberg and Eve Krakowski, “Introduction: A Handbook for Documentary Geniza Research in the Twenty-First Century,” in “Documentary Geniza Research in the Twenty-First Century,” eds. Goldberg and Krakowski, special issue, Jewish History 32 (2019): 118, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10835-019-09338-y. ↩︎

S. D. Goitein already recognized the effects of this acculturative process on Cairo Geniza texts in the 1960s. S. D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Genizah (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 1: 19. ↩︎

When “berakha” (blessing) does not appear in the heading of these specific entries it can refer to the week of the final parsha reading “[Ve-Zot Ha-]Berakha.” ↩︎

The abbreviation “ת׳׳ע / t[asāwī] ʿa[la]” in Judeo-Arabic translates as “amounting to” and thus precedes many numerical values (in this case to introduce monetary contributions). ↩︎

See Steffy’s collection of Judeo-Arabic register fragments on the Scribes of the Cairo Geniza site: https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/judaicadh/scribes-of-the-cairo-geniza/collections/citsci-rancho/multi-page-arabic-document-with-seal. ↩︎

I thank my colleague at the Princeton Geniza Lab, Alan Elbaum, for his comments on this translation. ↩︎

For insight onto the precarious position of Cairo’s Jewish and other minority communities during the French occupation, see especially: Gabriel Baer, “Popular Revolt in Ottoman Cairo,” Der Islam 52, no. 2 (1977): 221–26. ↩︎

Unlike the Western Arabic numerals that we use today in English, early modern Geniza fragments make extensive use of Eastern Arabic numerals. The latter system first developed across the Indian subcontinent and passed into Persian, Arabic, and Turkish recordkeeping practices in Late Antiquity and during the Middle Ages. ↩︎

For example, see ENA 330.3, Subject 12498819: https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/judaicadh/scribes-of-the-cairo-geniza/talk/1029/536401?comment=1575953&page=1. ↩︎

This seal clearly incorporates the name “Ibrāhīm / ابراهيم.” One possible reading of the letters below it is the surname “ʿAbīd / عبيد.” Much of the upper half of the seal is obscured by entries in the communal register but may contain an official and/or honorific title. The seal may have belonged to the same person who signed the verso of ENA 624.20, dated 29 Muḥarram, 1181 AH (which is June 6, 1767 CE). ↩︎

The entry written over this stamp was recorded in the week of the Va-Yelekh parsha reading in the Jewish calendar year 5559 AM, which was September 29–October 5, 1799. ↩︎

Marina Rustow, The Lost Archive: Traces of a Caliphate in a Cairo Synagogue (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 73–82. ↩︎

This reference appears in line three of the second entry of ENA 624.20. MuḥsinʻAlī Shūmān cites the existence of this congregation by the early seventeenth century. MuḥsinʻAlī Shūmān, The Jews in Ottoman Egypt Until the Beginning of the Nineteenth Century / al-Yahūd fī Miṣr al-ʻUthmānīyah ḥatta awāʾil al-qarn al-tāsiʻ ʻashar, vol. 2 (Cairo: al-Hayʼah al-Miṣrīyah al-ʻĀmmah lil-Kitāb, 2000) 70, 102. Maurice Fargeon confirms that the “Torkia” synagogue still existed in Cairo in the 1930s. Maurice Fargeon, Les Juifs en Egypte: Depuis les Origines jusqu’à ce jour (Cairo: Imprimerie Paul Barbey, 1938), 200. ↩︎

Solomon Schechter, “Miscellany,” (lecture, The Genizah and Jewish Learning, Dropsie College, May 5, 1910), qtd. in Norman Bentwich, Solomon Schechter: A Biography (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1938), 161. ↩︎