Scribes

Data's Destinations: Three Case Studies in Crowdsourced Transcription Data Management and Dissemination

Introduction

Online crowdsourcing—a series of methods for engaging volunteers with STEM, humanities, and cultural heritage research—has rapidly matured between 2000 and 2021. These efforts have been led by research groups and platform designers like Zooniverse, platform designers like FromThePage, Omeka, PYBOSSA and Scripto, and cultural heritage institutions like the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) and Smithsonian Institution. Volunteers help researchers, journalists, conservationists, cultural heritage practitioners, and one another to gather data that contributes to real research, original art, policy, community health, and more. In this essay, we will focus on cultural heritage crowdsourcing, and transcription projects in particular. Typically, these projects invite volunteers to transcribe handwritten or printed materials produced with ornate type or typewriter documents that—due to slight irregularities of the type, faint ink, or use of thin papers like onion skin—are not amenable to handwritten text recognition (HTR) or optical character recognition (OCR).

Crowdsourced transcription projects generally fall into one of two categories: those that are structured around a particular research problem or question, and those that gather data to enhance search and discovery of materials for open-ended and ongoing purposes. Whereas many researchers want to extract particular pieces of information from datasets, such as water salinity and temperature from old ships logs to feed data into climate change models (Old Weather), most cultural heritage crowdsourcing projects gather transcriptions of entire documents to support as-yet-unstipulated research purposes. Their goal is to create pathways for discovery in one or more content management systems (CMS), the catalogs and/or other platforms that make metadata and images of original materials discoverable.

Transcriptions that reproduce the text on the page (as opposed to select pieces of data) have a variety of applications across numerous disciplines, and also have the power to solve two common challenges for researchers and the librarians and archivists who support them: 1) transcriptions speed up discovery, and 2) transcriptions can (if presented properly online) increase accessibility for those who cannot read the original handwriting, including those who are Blind or cognitively impaired and use a screen reader. Before we delve into a few case studies of organizations that have used crowdsourcing methods to generate text transcriptions for these purposes, we want to emphasize that while researchers and archivists alike want to foster discovery and accessibility, the barriers to achieving these goals through crowdsourcing are complex and not yet widely discussed.

it’s not right to invite people to help researchers and increase accessibility … if the resulting data aren’t made widely available

The number of galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (GLAM) institutions that have successfully integrated their crowdsourced transcription data into their core CMSs is far outweighed by those that have not yet found a workable solution, and many who have found solutions have used workarounds that are a stop-gap until better alternatives emerge. For example, a common workaround is to publish bulk data in an online repository on GitHub or a university library or research repository, while GLAM practitioners try to determine how to integrate data into their core CMS. Lucinda Blaser of Royal Museums Greenwich identified the absence of appropriate metadata fields in her institution’s CMS as a major barrier to integrating the Old Weather transcriptions.1 She and her colleagues were eager to use the data, but the metadata field they hoped to use had a character limit set by the vendor. Anne Bowser et al. expose the absence of norms and ongoing funding for data integration across citizen science crowdsourcing domains more broadly (including transcription projects), and highlight the ethical problems of not releasing crowdsourced data. They aver, and we agree, that it’s not right to invite people to “help researchers,” “increase accessibility,” and achieve other goals if the resulting data aren’t made widely available, as well as understandable—meaning that the methods of collection are well described.2

Ina-Maria Jansson and Chern Li Liew explore anxieties about crowdsourcing data quality among GLAM practitioners as well as members of the public, some of whom are anxious about whether crowdsourced data deserves a place in the authoritative record.3 Jansson and Liew’s findings are particularly disturbing, because they reveal that many institutions are actively engaged in crowdsourcing but still deeply uncomfortable with their own stated aims. These institutions are thus unlikely to hold up their end of the bargain with volunteers—namely making the data that volunteers produce available for research and enabling access. More work is needed to address concerns about data quality. Current approaches include:

- overcoming barriers to data publication and integration when people can see examples from peer institutions or trusted sources, they are likely to be reassured;

- data quality analysis studies that provide solid information about the transcription outcomes from different projects, and

- real talk about the quality of other data that is already in the authoritative record. For example, Victoria Van Hyning and her teammates at the Library of Congress (LOC) frequently pointed out to colleagues that the Library already publishes low-quality OCR in the authoritative record (often provided by vendors as part of their digitization package), and that crowdsourced transcriptions are typically of a much higher quality than this OCR.

If we can all more openly discuss and address these challenges and ways of meeting them, we will make better progress in supporting collections discovery and use, research, and novel applications of crowdsourced data.

data management planning is a necessary part of crowdsourcing

Crowdsourcing platform designers Ben and Sara Brumfield are also drawing attention to these issues as they affect scholarly editors and cultural heritage practitioners, and are working on some new solutions to data unification, publication, and discovery. In a recorded talk to the International Interoperable Image Framework (IIIF) conference in 2021, they demonstrate how content from digital scholarly editions can move between multiple systems like Fedora or ContentDM to FromThePage, where the images are transcribed by volunteers and/or an editorial team, and then back to a scholarly editing platform such as Omeka-S, all with the help of IIIF-compliant metadata and images. They discuss how scholarly edition materials might then feed back into the original CMS via the same IIIF metadata, in order to enhance the materials and increase discovery on the host institution’s CMS. They conclude their piece by announcing work on a new feature that will “allow editors to export stand-alone web-pages for minimal computing needs and digital preservation” in cases where there isn’t an institutional CMS amenable to this kind of roundtripping of the data.4

Case Studies

The remainder of this essay offers three case studies of projects that showcase different successes and challenges in crowdsourced transcription data integration. Our early-stage research reveals that the challenges facing these projects are more widely shared by a range of crowdsourcing stakeholders, including platform designers, academics, cultural heritage practitioners and the vendors who create CMSs for cultural heritage organizations. Van Hyning was directly involved in each project. These case studies include Shakespeare’s World (SW), which launched on the Zooniverse platform in 2015 and was sunset in 2019. It was a partnership between Zooniverse, the Folger Shakespeare Library and the Oxford English Dictionary (OED). The By the People project (BTP) was launched by the Library of Congress (LOC) on a bespoke platform called Concordia in 2018, and the David C. Driskell Papers Project was created by Van Hyning, six MLIS students, and their colleagues at the David C. Driskell Center at the University of Maryland on the FromThePage platform in 2020, and launched in 2021. All of these were produced by multidisciplinary teams involving cultural heritage practitioners such as archivists, metadata specialists, curators, and academics from STEM and/or humanities backgrounds. Some projects involved students, while others involved formal project managers, web developers and database engineers (system designers). The projects were built on three different crowdsourcing platforms, all of which are separate “pass-through” applications that are not directly connected to the relevant cultural heritage institution’s CMS. The datasets in each case require some dedicated effort to move the content out of the crowdsourcing platform and into the CMS to appear alongside the digital images of the original documents, and thus make them searchable down to the page level.

Shakespeare’s World

In this case study we’ll outline some successes of SW before coming on to the challenges of data aggregation that arose on the Zooniverse side, and the data integration challenges that arose on the Folger side. The quality of the research and engagement outcomes are significant, and bring home the ways in which the SW team’s struggles with data wrangling curtailed our overall rate of discovery. However, the data challenges the team encountered, and the enormous efforts that collaborators have spent to address these (including major updates to the Zooniverse platform and the development of numerous codebases and processes to clean the data) are important research activities and outcomes in their own right.

The goals of Shakespeare’s World (SW) were to:

- Engage a broad volunteer base to transcribe digitized Folger manuscripts from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, to make the manuscript contents amenable to full-text search;

- Engage early modern literature and history scholars, especially those with strengths in women’s history, history of science, food, and medicine, with crowdsourcing as a means to help them identify new materials for their research;

- Identify previously unrecorded words, variants, and older usages of words for the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), and

- Try out new approaches to transcription on the Zooniverse platform.

The project achieved these goals to varying degrees. It exceeded our expectations in terms of engagement, particularly regarding how volunteers engaged with researchers and the OED team. Thousands of volunteers transcribed, discussed, and conducted research about early modern manuscripts, history, language, and culture, thereby gaining or enhancing research and paleographical skills they might not otherwise have had the opportunity to develop. Together with volunteers, the team helped advance the research agendas of six scholars, resulting in a half dozen publications that cite the contributions of volunteers. The team also encountered unexpected challenges relating to the data outputs of the project, which in turn led to new avenues of research at Zooniverse from 2016 to the time of writing, as well as a long-running effort to make the SW data usable.

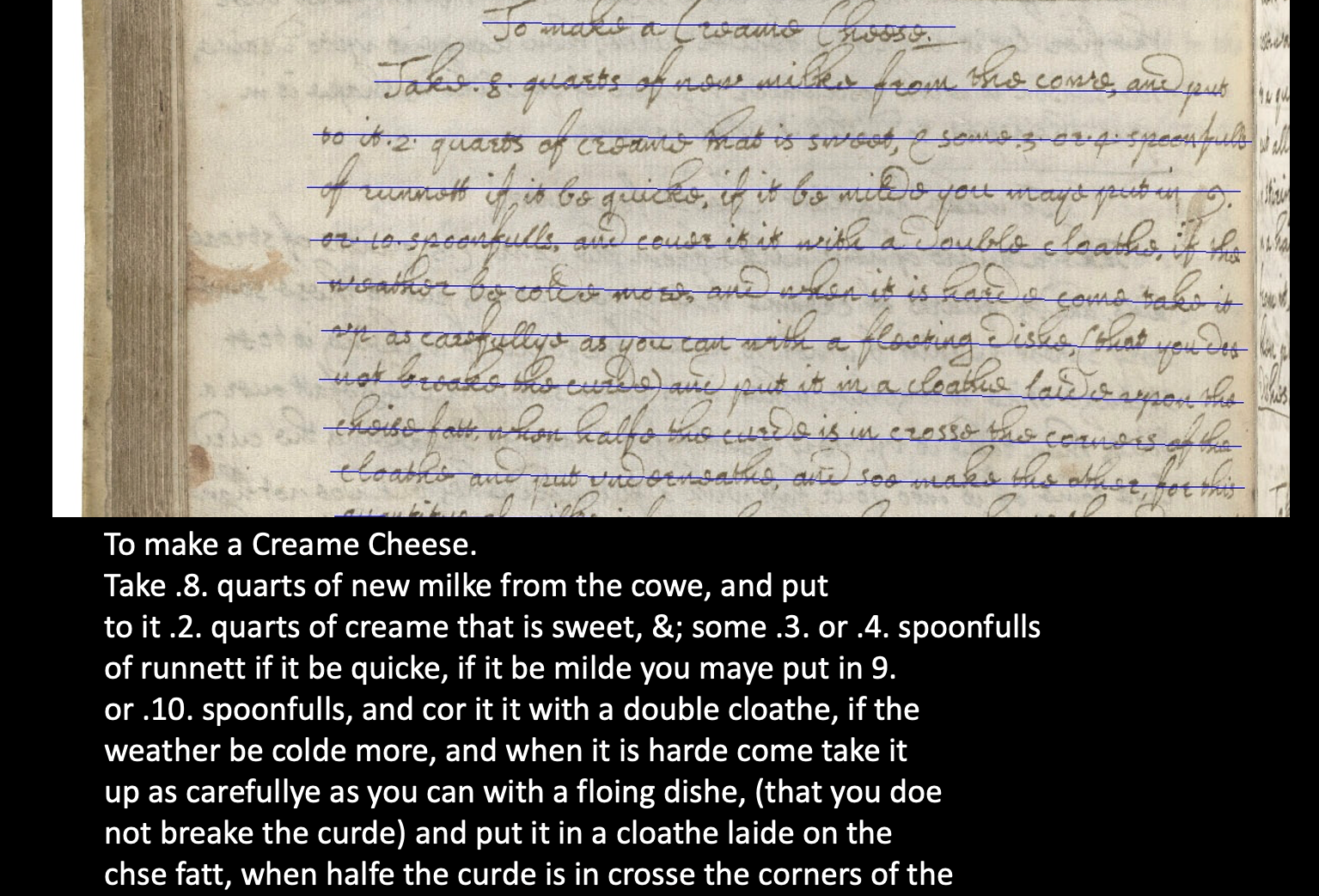

Volunteer transcription of an early modern creame cheese recipe.Shakespeare’s World

Engagement Successes: Volunteers, Scholars, and the OED

Shakespeare’s World attracted 3,926 registered volunteers, as well as anonymous participants (numbers unknown), who transcribed 11,490 digital images of manuscript pages (single and double page spreads) over a period of nearly four years (2015-2019). These included letters, recipes, and newsletters, an early form of manuscript newspaper delivery service that was curated for particular recipients.

major updates to the Zooniverse platform and the development of numerous codebases and processes to clean the data are important research activities and outcomes in their own right.

Volunteers identified several words that were not previously included in the OED, as well as a ninety-year antedating of “partner” in the sense of spouse or lover, and a nearly two-hundred-year antedating of “white lie.” The Shakespeare’s World Talk board (a discussion forum for the project) was a vital space for what guest researcher Lisa Smith described as a form of collective close reading (close reading is a widely used form of literary analysis typically conducted by solo researchers).5 To take just one example of collective close reading and research from SW Talk, the team present the case of “taffytie tartes.”6 This phrase was identified by volunteer @kodemunkey just eight days into the project. Lively discussion as to its exact meaning blossomed on Talk, as volunteers, early modern recipe researchers including Smith, Folger and Zooniverse staff, as well as OED Deputy Editor Philip Durkin shared evidence from the OED, other SW recipes, and their own research.7 Durkin described our community process in a blog post, offering etymological starting points for the meaning of Taffytie (linking it to taffeta fabric), and a reflection on the value of our endeavor. He wrote:

The sources featured in Shakespeare’s World are particularly interesting and valuable for OED lexicographers. We have relatively easy access to a good deal of printed material from this period, now increasingly searchable in electronic collections. It is much harder for OED’s lexicographers to survey patterns of use in manuscript sources from this period, which often differ in interesting ways from printed sources—this can be in small features like spelling (as for instance taffytie), as well as in reflecting aspects of life (such as culinary recipes) that are relatively under-represented in the printed sources, or only appear there in a rather different light. This project therefore offers a new way in to some material that has previously been underexploited in tracing the history of English.8

In order for “taffytie tartes” to be included in the OED the editorial team needed additional evidence, and in particular dated evidence, which can be harder to derive from manuscript sources like recipe books that created for everyday practical use in family homes for ongoing use. Volunteers kept up their search on Shakespeare’s World and a few years later Van Hyning expanded the hunt for additional sources by reaching out to Mary-Anne Boermans, a finalist on the Great British Bake Off Season 2. Van Hyning was intrigued by Boermans’s historically informed baking practice, and had a hunch that Boermans might have come across taffety tartes in her research, and whether she’d be interested in the recipes from Folger.9 Boermans had come across several recipes and had already included one in her first cookbook Great British Bakes: Forgotten Treasures for Modern Bakers (2013), but, as she wrote in a blog post for the Folger in 2019, many of the recipes she’d found were missing crucial information as to what made a Taffety Tart a Taffety Tart. The presence of thirteen recipes at the Wellcome confirmed that taffety tarts “were very much a ‘thing’ in seventeenth-century food fashion. Trying to define what exactly this ‘thing’ was, however, was more complicated than I first imagined.” The Folger examples provide crucial missing evidence about the fillings, pastry type, shape, bake time, temperature and decorative features:

It is almost a ‘complete package’ in terms of the details supplied, needing only to have been dated and include a drawing of the pastry shape in order to complete the picture. It might not be the jigsaw box cover image, but it’s definitely the four corner pieces of the puzzle, because it reveals that what this Jacobean pastry most resembles, with its thin, rectangular shape, fruit filling and icing is… a pop-tart. A seventeenth-century pop-tart.10

Boermans kindly baked four different examples and shared images of her work:

Boermans also supplied dated manuscript evidence, which means that “Taffety” was added to the OED in 2018.11

Shakespeare’s World Data Cleaning and Release

SW was always meant to be fun and inclusive: a place where people could learn about subjects and people they might never have considered. The SW team very consciously emphasized that volunteers could take part in—and even lead—discovery and research impact through the OED partnership, and also tried to make the transcription task itself as accessible to beginners as possible. The team hypothesized that by letting people choose to transcribe as little as a word or line they would only contribute what they felt confident reading, and that, in keeping with the broader Zooniverse methods of promoting nonspecialist engagement and multiple independent classifications followed by aggregation, the project would make crowdsourced transcription accessible and welcoming in new ways. This proved true, based on the feedback via Talk and other venues, but unfortunately the complexities of transcription—the slight differences of interpretation from one user to another, stemming from genuine ambiguities present in most documents rather than user mistakes—combined with the imprecision of clustering closely written lines of text, rendered much of the output data very difficult to use.

Each word on each page was independently transcribed by three or more people, and their transcriptions were compared and combined using a clustering algorithm and a genetic sequencing algorithm.12 Our early aggregation testing was based on gold standard data produced by project staff at Folger, against which they compared transcriptions produced by Zooniverse staff, who included an early modernist with paleography expertise (Van Hyning) as well as folks without paleography training, including astronomers and developers, many of whom hold higher degrees in other fields including philosophy, ecology, and computer science. The project team also gathered transcription data from the pool of Zooniverse beta tester volunteers, a subset of the wider Zooniverse user community who test projects under development. Early aggregation results were promising, showing approximately 98 percent agreement between transcribers in many cases. But as the project went public and the heterogeneity of both the participants and the documents increased, clustering accuracy dipped, which negatively impacted text string comparison. In retrospect, it’s clear that our beta testing sample was too skewed towards people with higher degrees, relevant subject knowledge, and/or existing familiarity with the Zooniverse platform.

Thousands of volunteers transcribed, discussed, and conducted research about early modern manuscripts, history, language, and culture … [in] a form of collective close reading

From 2016 to 2018, the team made several attempts to improve aggregation for SW and the numerous transcription projects that also used similar methods of transcription (i.e. AnnoTate with Tate Britain, and Decoding the Civil War with the Huntington). The project had some success, but the overall results still require significant editing. For three years this was done by grant-funded staff at Folger. In 2021, SW Co-Investigators Heather Wolfe and Van Hyning worked with colleagues at Folger and the University of Maryland iSchool’s iConsultancy undergraduate capstone students on a SW data cleaning project.13 The students used the most recent iteration of aggregated data provided by Zooniverse, and focused on stripping out duplicate lines of text, which was one of the most common errors introduced by aggregation (this is based on visual inspection by former Folger palaeographer Sarah Powell, and SW Co-Is Wolfe and Van Hyning, rather than a full formal analysis of the data. Further quantitative analysis of different stages of SW data is planned for the future).

This level of intervention certainly allays any anxieties about quality control, and can be seen as the gold standard for cultural heritage practitioners wishing to present accurate and highly authoritative information to their patrons. However, this level of transformation and encoding is prohibitively labor intensive even without unexpected data-cleaning challenges. For this reason, since February 2019, Folger has started making plain text transcriptions available on their main discovery platform, a lightly customized off-the-shelf instance of Luna (luna.folger.edu). According to Folger metadata librarian Emily Whal, they added a transcription “‘Facet Search’ button on the collection home page [that] take[s] you to a list of the call numbers available in the collection.”14 On Luna, SW transcriptions join approximately 19,000 transcriptions produced on Folger’s in-house transcription system called Dromio, which was developed over fifteen years ago by Folger developer Mike Poston for Wolfe’s palaeography classes. Dromio continues to support pedagogy, as well as transcribathon events. As of October 2021, 7,271 SW transcriptions have been edited into these three presentations, encoded with TEI P-4 markup and published for search and download on the Early Modern Manuscripts Online (EMMO) platform (emmo.folger.edu). Over 12,500 transcriptions have been incorporated into Luna.15 To get to Luna, SW transcriptions that have been tidied up by the UMD students, but that haven’t gone through the EMMO treatment, are uploaded to the FromThePage crowdsourcing platform and edited by Folger docents, volunteers, and staff. In other words, the crowdsourced data are going through a further phase of crowdsourced editing. The SW transcriptions in Luna are not the same documents (yet) as those in EMMO.

Each word on each page was independently transcribed by three or more people, and their transcriptions were compared and combined using a clustering algorithm and a genetic sequencing algorithm.

Both the successes and the challenges of Zooniverse transcription approaches on SW and its sister project AnnoTate led to important developments for the platform. The first was a successful grant bid to the IMLS in 2016 to develop new approaches to text transcription, explicitly to test whether collaborative or independent methods were more accurate. This supported the development of Scribes of the Cairo Geniza and Anti-Slavery Manuscripts, and subsequent publications about data quality and volunteer engagement in independent versus collaborative methods of transcription.16 Additional grant-funded work led by Samantha Blickhan resulted in a new text aggregation editing tool called ALI/CE.

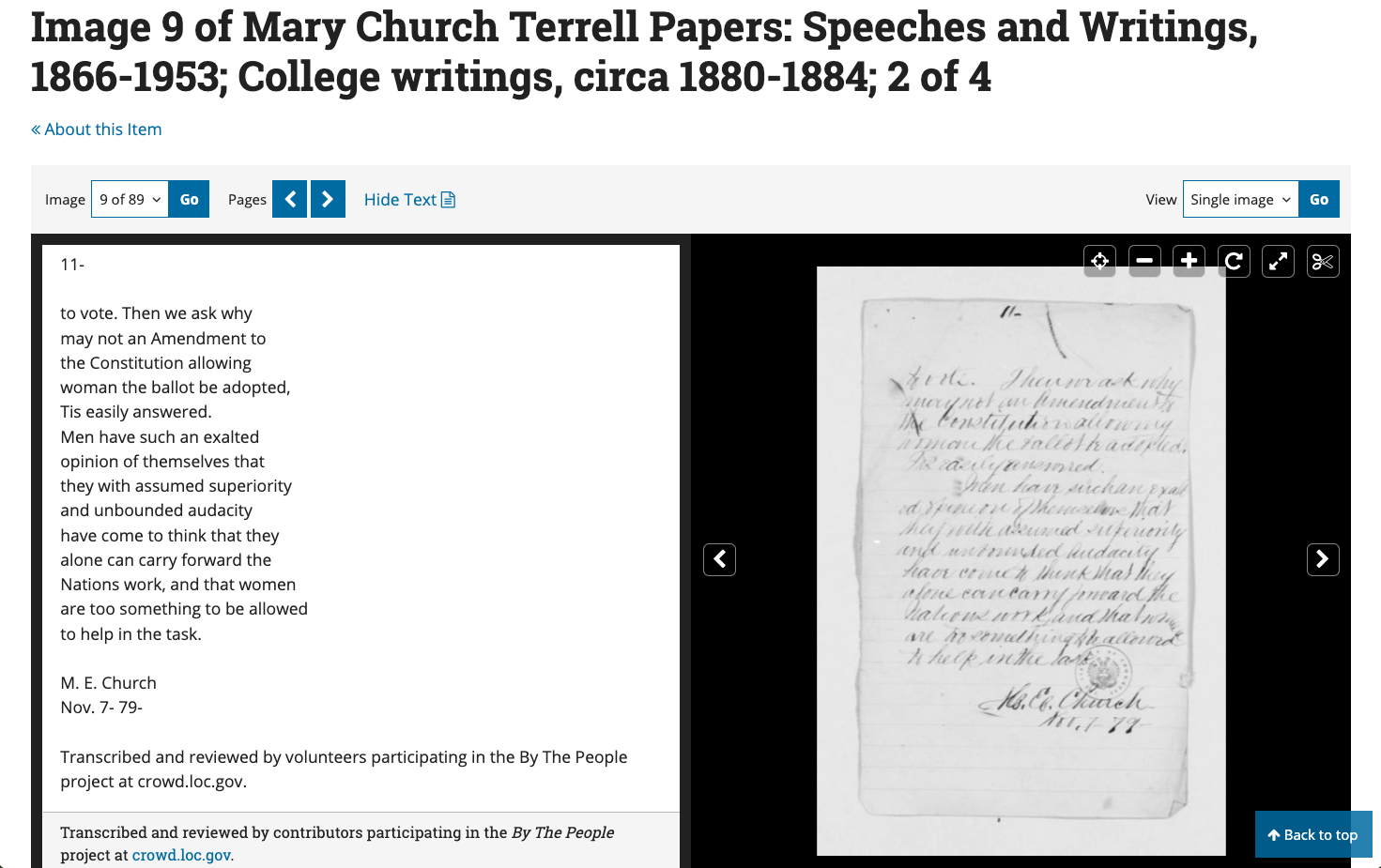

By the People

Our next case study is the Library of Congress (LOC) By the People (BTP) crowdsourced transcription project. BTP features materials from across the LOC’s Special Collections divisions (Manuscript, Rare Book, Folklife, and others). These are arranged into “Campaigns” and presented to volunteers along with transcription conventions, a discussion platform, and explanatory material to help folks learn a bit about the subjects of the documents. These range from the papers of Rosa Parks, to those of presidents Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt, and ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax. Despite the heterogeneity of the documents that pass through the platform, and indeed the heterogeneity of metadata models within the LOC, the data outputs from the project are fairly easy to work with, and the rate of data publication has been fairly fast. BTP relies on volunteers being able to peer-review one another’s transcriptions. Pages can be transcribed and edited by multiple volunteers before being marked as “complete.” This review system enables collaboration between transcribers, and between transcribers and the LOC staff who support BTP.

Thanks to the foresight and advocacy of various stakeholders at the LOC, the project was well staffed and resourced from the outset and included provision for full-time community managers, a team of developers, user experience specialists, metadata specialists, and accessibility experts. The project’s transition from a “pilot” effort funded through gift money, to “core infrastructure” funded through congressional appropriations, more than a year ahead of schedule, has been cited by Ben Brumfield of FromThePage as evidence for the “maturity of the [crowdsourcing transcription] methodology.”17

Although the project was built on a separate transcription platform, the expectation from the start was that the data should return to loc.gov

Part of the success of BTP stems from LOC staff’s ability to publish the transcriptions. Although the project was built on a separate transcription platform, the expectation from the start was that the data should return to loc.gov (the Library’s main web property and discovery system) early and often. Our first data round-trip occurred less than three months after launch, and consisted of 781 pages from across the five original campaigns.18 The BTP team and stakeholders worked together to identify a data pathway, including relevant metadata fields, on-screen presentation, appropriate language to describe and acknowledge volunteer efforts, and important internal questions about custodial responsibility for the data over time. The project team went into this process aware of the challenges, but also aware of possible workarounds and solutions. The incorporation of OCR into loc.gov was a helpful precedent, as was the fact loc.gov is a bespoke system maintained by a team of internal engineers and developers.

Though glad of this early success, the team quickly learned from users who consulted manuscripts online that it was confusing when some pages in a letter or journal were transcribed and others were not. The team thought it was best to publish any data when it became available, but user feedback revealed it was best to wait until full documents are done. So the team changed their approach from March 2019 onward, waiting until entire Campaigns of documents (i.e. the Branch Rickey papers or Rosa Parks’s papers) are completed, before the results are ingested into loc.gov.19

Screenshot of By the People, showing transcription of a document from the Mary Church Terrell Papers.Library of Congress

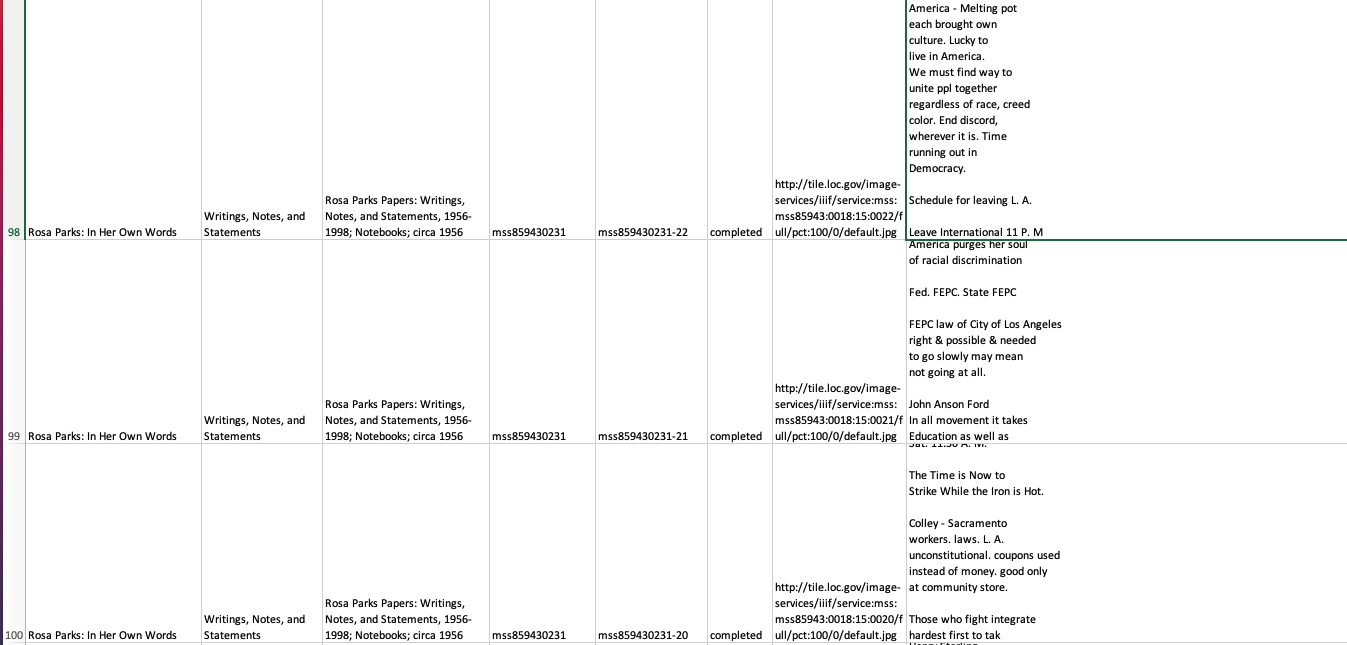

Of the over 620,000 documents made available on BTP since October 2018, roughly 392,000 pages have been transcribed, reviewed, and marked as complete by volunteers, and 63,400 have been incorporated into loc.gov. The data are published in two ways. First, the transcriptions are embedded in the metadata for individual pages as well as full documents. They appear alongside the images of the original manuscripts, thus creating pathways to individual pages. These transcriptions can be downloaded as .txt files either one page at a time or as whole documents. An attribution to the volunteers appears in two places, first as an overlay in the on-screen display for each page, and embedded in the .txt transcription file itself: “Transcribed and reviewed by volunteers participating in the By The People project at crowd.loc.gov.” The second way that LOC makes the transcriptions available is as bulk datasets consisting of a .CSV file and README file detailing the context in which the data were originally collected on BTP. Bulk datasets have different affordances from individual .txt files.

Screenshot of bulk dataset from Rosa Parks Papers in By the People project.By the People (LOC)

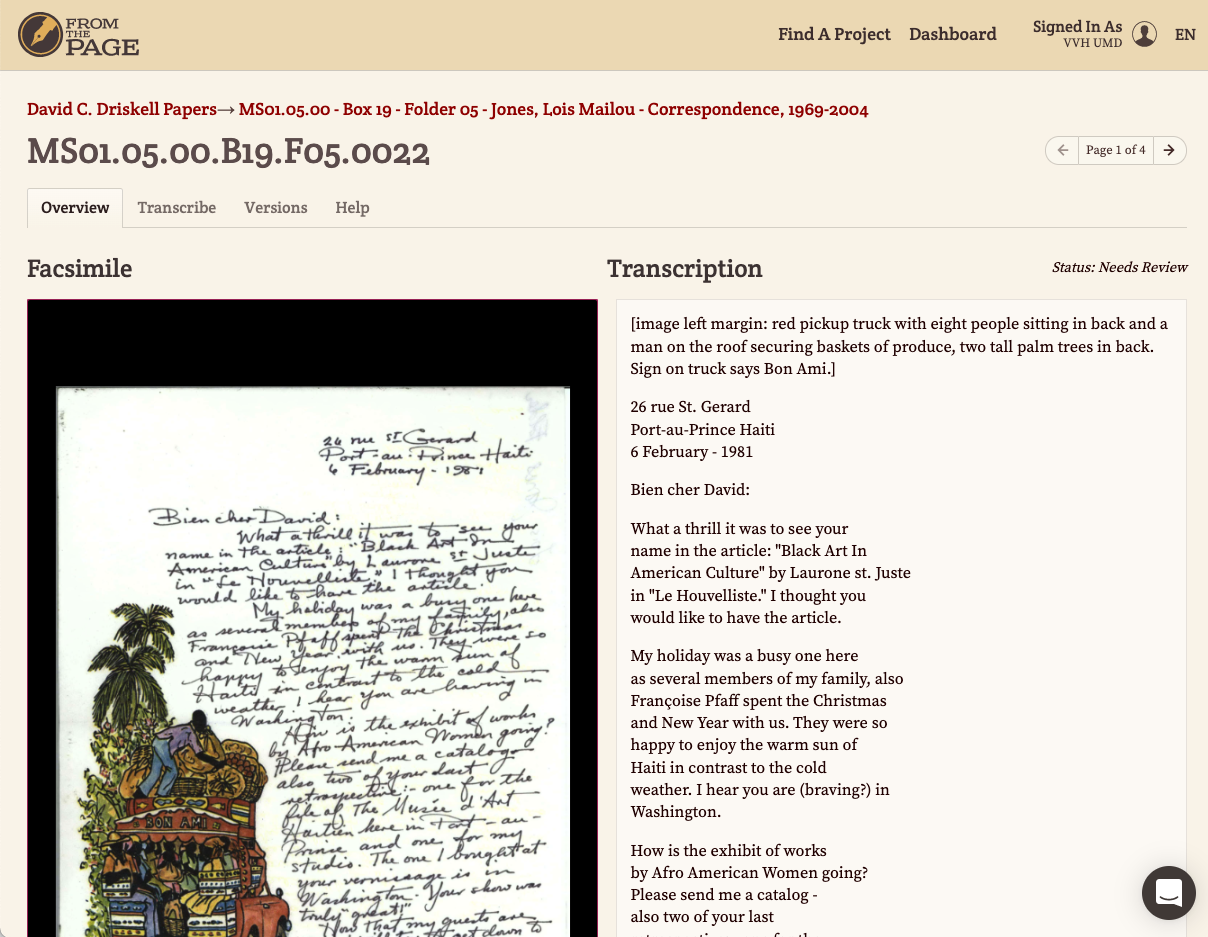

The David C. Driskell Papers Project

Our final case study features a project devoted to the legacy of the late David C. Driskell, professor emeritus of art and art history at the University of Maryland. The University of Maryland’s David C. Driskell Center (DCDC) is an art gallery, archive, and educational center founded with the central mission of celebrating Black artists and art history. It was founded by colleagues of Driskell after his retirement, as a mark of respect and admiration for his incredible contributions to art history, education, and artistic production. Driskell was an American artist and educator who was instrumental in establishing Black art as a scholarly field of study: he generated a significant correspondence with leading artists including Alan Porter and Georgia O’Keefe, as well as his students and mentees.

Professor Driskell died due to complications of Covid-19 on April 1, 2020. In order to celebrate and remember this fixture of both the University of Maryland and of the art community, Van Hyning collaborated with colleagues at the Driskell Center, and six MLIS students to create a crowdsourcing project on the From the Page platform featuring his archives, such as letters and journals. The David C. Driskell Papers Project (DCDPP) is hosted within the Driskell Center as an online crowdsourced transcription project hosted in the FromThePage platform. The transcription project exists alongside an exhibit of Driskell’s papers also hosted by the DCDC. While not immediately related, both the transcription project and the exhibition existed to celebrate the life of Driskell and invite the public to share in the memory of his life and legacy.

Driskell was an American artist and educator who was instrumental in establishing Black art as a scholarly field of study

The transcription project focuses predominantly on the written documents contained within the curated collection of personal papers. The team endeavored to make Driskell’s personal papers and the accompanying transcriptions easily accessible to best serve both an informational role and an accessibility role for researchers attempting to learn more about his life and the impact of his efforts to raise awareness of the quality, quantity, and vibrancy of Black art in America and abroad. The project launched in February 2021 with a corpus of over 1,200 documents, and additional materials have been uploaded since. Volunteers and some of the original project team have transcribed over 1,300 pages of documents and staff have begun work on indexing these transcriptions following review and OCR corrections.

But for all the ease of using FTP to produce usable transcription data for the digitized objects in the collection, there were known issues from the outset when it came to the storage and presentation of the transcription data on the DCDC’s existing CMS. The DCDC employs PastPerfect, a CMS that is typically used by museums and galleries to catalog and describe physical objects rather than archives. This software is designed with the stated intent to be used in all manner of cultural heritage institutions, not just galleries or museums. PastPerfect’s own website says that “over 11,000 museums, historical societies, archives, libraries, and other collecting institutions worldwide have purchased PastPerfect Museum Software since its first release in 1998”; however, the fundamental structure of PastPerfect is not ideal for archival metadata structures and arrangement.20 The system assumes that each record pertains to one physical item such as a painting or sculpture, for which a few photos will suffice, but an archival item might consist of hundreds of pages, and there might be numerous items in a given folder or box which are not described at the item much less the page level. The record structure isn’t granular enough. Furthermore, other than a notes field, there is no space within the PastPerfect CMS to represent transcription data. To use a notes field in this system, the DCDC archivist would have to manually upload each transcription, which is too labor intensive for this organization.

The project team knew about these issues prior to creating the DCDPP crowdsourced transcription project, as they are common in the GLAM community. Even highly specialized repositories tend to have a mixture of formats that most CMSs don’t quite cater to. The Zooniverse project AnnoTate (2015–2019), with Tate Archive, was designed to produce transcription data for a bespoke CMS that unites object and archival records. They embarked on DCDPP in part to gain insights and data for our ongoing conversations about how best to serve the heterogeneous materials housed at the DCDC. Crowdsourcing projects, especially smaller scale pilot projects, can empower cultural heritage institutions to experiment with incorporating more diverse and nontraditional data into their CMSs, and hopefully also give them the data they need to advocate for their needs to vendors who supply those systems. While the larger questions of CMS type unfold, the team can publish the Driskell data in a number of venues, including the DCDC’s main website or the Digital Repository of the University of Maryland (DRUM).

Integrating Solutions for Transcription Data

Regardless of how crowdsourced data are managed and made available, data management planning is a necessary part of crowdsourcing, and conversations about how to achieve data publication or integration should start as early as possible. Solving these questions ahead of launch, and preparing for potential content management issues, can ensure that projects meet the institutional or individual’s vision more effectively. If you’re a GLAM practitioner using an off-the-shelf CMS, talk to your vendor. Find out if your license or product level includes a capacious enough field for transcriptions. Find out whether you can import content in bulk or whether you have to cut and paste transcriptions one at a time. Be up front with your volunteers about your ambitions for the data, as well as current limitations.

Archives typically arrange and describe materials at the level of items (the journal, the letter) or boxes (a collection of folders with letters from various correspondents) rather than pages, whereas transcriptions bring us right down to the page level.

As institutions such as the Folger have begun ingesting their data, we’ve learned more about the widespread challenges of ingesting long runs of text into CMSs—no matter how clean the data from crowdsourcing platforms are—whether these are off-the-shelf products or bespoke systems created by institutions. Sometimes metadata managers can shoehorn transcriptions into a field without a character count limit, but the status of the transcriptions within archival description is uncertain and still emerging. Archives typically arrange and describe materials at the level of items (the journal, the letter) or boxes (a collection of folders with letters from various correspondents) rather than pages, whereas transcriptions bring us right down to the page level. The technical fixes may be relatively simple, but there’s a much more significant shift that needs to happen at the level of archival practice and cultural norms.

Data publication can take a wide variety of forms in order to meet the varying demands for different projects and the visions of different institutions hosting a crowdsourced transcription project. There may not be a one-size-fits-all solution, especially when we consider that most institutions have quirky ways of describing rare materials in the first place—quirks that are shaped by the materials themselves, the many layers of metadata that accrue to objects over time, and the affordances and limitations of different CMSs. Whatever the quirks, though, crowdsourced data deserves a place in the authoritative record. Data can be posted in bulk as .CSV files on institutional webpages, GitHub, Internet Archive or other repositories, and/or in metadata fields that connect the transcription directly to the image in question. Data should also, ideally, be publicized and described in articles and blog posts where they may reach a wide range of potential users—the Journal of Open Humanities Data is one such venue (Van Hyning serves on the editorial board of the Journal, Jones as a copyeditor). Collaborators on the Scribes of the Cairo Geniza project do a blend of several of these approaches for the Scribes of the Cairo Geniza data. A stopgap to these solutions would be a simple note in a metadata field, a finding aid, and/or on an institution’s website saying that transcription data for a given page, document, or collection can be made available upon request. This would enable institutions to better meet the needs of Blind users or others who use screen reader technologies to access web-based written content. This would be a move towards 508 compliance, specifically making projects and their outputs more accessible to people who use screen readers.21 If organizations doing crowdsourced transcription have concrete plans for data storage and accessibility at the outset of the project, they will be in a stronger position to achieve Web Content Accessibility Guide (WCAG 2.0 or 2.1) compliance in the transcription data display.

Bibliography

Blaser, Lucinda. “Old weather: Approaching collections from a different angle.” In Crowdsourcing Our Cultural Heritage edited by Mia Ridge, 45-56. Routledge: New York, 2014.

Blickhan, Samantha, Andrea Simenstad, Amy Boyer, Daniel Hanson, Coleman Krawczyk, and Victoria Van Hyning. “Individual vs. Collaborative Methods of Crowdsourced Transcription.” Journal of Data Mining & Digital Humanities Special Issue on Collecting, Preserving, and Disseminating Endangered Cultural Heritage for New Understandings through Multilingual Approaches (December 3, 2019). https://jdmdh.episciences.org/5759/pdf.

Boermans, Mary-Anne. “Taffety Tarts: How a 17th-Century Pastry Made It into the OED.” Blog. Shakespeare & Beyond, March 26, 2019. https://shakespeareandbeyond.folger.edu/2019/03/26/taffety-tarts-folger-manuscript-recipes-17th-century-pastry-oxford-english-dictionary/.

Bowser, Anne et al. “Still in Need of Norms: The State of the Data in Citizen Science.” Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 5, no. 1 (September 4, 2020): 18. https://doi.org/10.5334/cstp.303.

Brumfield, Ben. “The Decade in Crowdsourcing Transcription” From the Page (blog). January 9, 2020. https://content.fromthepage.com/decade-in-crowdsourcing/.

Brumfield, B., & Brumfield, S. (August 30, 2021). More Than Round Trip: Using Transcription for Scholarly Editions and Library Discovery. https://content.fromthepage.com/using-transcription-for-scholarly-editions-and-library-discovery/

Concordia Codebase, https://github.com/LibraryOfCongress/concordia

Durkin, P., 2017. Release notes: a big antedating for white lie - and introducing Shakespeare’s world. Oxford English Dictionary, 28 September 2017. Available at https://public.oed.com/blog/september-2017-update-release-notes-white-lie-and-shakespeares-world/ [Last accessed 30 June 2021].

Durkin, P., 2015. Our First Discovery! And a brief history of the Oxford English Dictionary. Shakespeare’s World. Available at https://blog.shakespearesworld.org/2015/12/17/our-first-discovery-and-a-brief-history-of-the-oxford-english-dictionary/ [Last accessed 30 June 2021].

Jansson, Ina-Maria. “Organization of User-Generated Information in Image Collections and Impact of Rhetorical Mechanisms.” Knowledge Organization 44, no. 7 (September 30, 2017): 515–28.

Liew, Chern Li. “Social Metadata and Public-Contributed Contents in Memory Institutions: ‘Crowd Voice’ Versus ‘Authenticated Heritage’?” Preservation, Digital Technology & Culture 45, no. 3 (October 1, 2016): 122–33. https://doi.org/10.1515/pdtc-2016-0017.

Oxford English Dictionary. “December 2018 Update: Taffety Tarts Enter the OED,” December 13, 2018. https://public.oed.com/blog/december-2018-update-taffety-tarts-enter-oed/.

Van Hyning, Victoria. “Finding By the People Transcriptions in the Library’s Digital Collections,” The Signal,” July 9, 2020. https://blogs.loc.gov/thesignal/2020/07/finding-by-the-people-transcriptions-in-the-librarys-digital-collections/ .

Van Hyning, Victoria. “Harnessing Crowdsourcing for Scholarly and GLAM Purposes.” Literature Compass 16, no. 3–4 (2019): e12507. https://doi.org/10.1111/lic3.12507.

Lucinda Blaser, “Old Weather: Approaching Collections from a different angle,” in Crowdsourcing Our Cultural Heritage, ed. Mia Ridge (New York: Routledge, 2014), 45–56. ↩︎

Anne Bowser et al., “Still in Need of Norms: The State of the Data in Citizen Science,” Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 5, no. 1 (September 4, 2020): 18, https://doi.org/10.5334/cstp.303. ↩︎

Ina-Maria Jansson, “Organization of User-Generated Information in Image Collections and Impact of Rhetorical Mechanisms,” Knowledge Organization 44, no. 7 (September 30, 2017): 515–28, https://www.ergon-verlag.de/isko_ko/downloads/ko_44_2017_7_f.pdf; Chern Li Liew, “Social Metadata and Public-Contributed Contents in Memory Institutions: ‘Crowd Voice’ Versus ‘Authenticated Heritage’?” Preservation, Digital Technology & Culture 45, no. 3 (October 1, 2016): 122–33, https://doi.org/10.1515/pdtc-2016-0017. ↩︎

Sara Carlstead Brumfield and Ben Brumfield, “More Than ‘Round Trip’: Using Transcription for Scholarly Editions and Library Discovery,” July 20, 2021, video, 2021 IIIF Conference, June 22, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mlYvbOX4K5g&t=8s. ↩︎

Smith, Lisa. “On Close Reading and Teamwork.” Shakespeare’s World (blog), February 3, 2016. https://blog.shakespearesworld.org/2016/02/03/on-close-reading-and-teamwork/. ↩︎

Because there was no completely standardized spelling in English before the eighteenth century, multiple spellings of the word “taffytie tartes” appear in this paper as a reflection of the various ways the authors of the manuscripts referred to them. Manuscript spelling tended to be even more varied than print. For a brief history of English spelling and pronunciation see Oxford English Dictionary. “Early Modern English Pronunciation and Spelling,” August 16, 2012. https://public.oed.com/blog/early-modern-english-pronunciation-and-spelling/. ↩︎

“Taffytie,” Shakespeare’s World Talk (forum), Zooniverse, https://www.zooniverse.org/projects/zooniverse/shakespeares-world/talk/search?query=taffytie. ↩︎

Philip Durkin, “Our First Discovery! And a brief history of the Oxford English Dictionary,” Shakespeare’s World (blog), Zooniverse, May 8, 2018, https://blog.shakespearesworld.org/2015/12/17/our-first-discovery-and-a-brief-history-of-the-oxford-english-dictionary/. ↩︎

Victoria Van Hyning, May 31, 2018, comment on Mary-Anne Boermans, “Me,” Time to Cook–Online (blog), https://timetocookonline.com/title/#comment-39337. ↩︎

Mary-Anne Boermans, “Taffety Tarts: How a 17th-Century Pastry Made It into the OED,” Shakespeare & Beyond (blog), Folger Shakespeare Library, March 26, 2019, https://shakespeareandbeyond.folger.edu/2019/03/26/taffety-tarts-folger-manuscript-recipes-17th-century-pastry-oxford-english-dictionary/. ↩︎

Philip Durkin, “December 2018 Update: Taffety Tarts Enter the OED,” OED Blog, December 13, 2018, https://public.oed.com/blog/december-2018-update-taffety-tarts-enter-oed/. ↩︎

Victoria Van Hyning, “Harnessing Crowdsourcing for Scholarly and GLAM Purposes.” Literature Compass 16, no. 3–4 (2019): e12507, https://doi.org/10.1111/lic3.12507. ↩︎

That project is available at https://github.com/nisaputri/The-Shakespeares-UMD ↩︎

Emily Whal, email message to Van Hyning, October 14, 2021. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Samantha Blinkhan et al., “Individual vs. Collaborative Methods of Crowdsourced Transcription,” in “Collecting, Preserving, and Disseminating Endangered Cultural Heritage for New Understandings through Multilingual Approaches,” eds. Amel Fraisse, Ronald Jenn, and Shelley Fisher Fishkin, special issue, Journal of Data Mining and Digital Humanities (2019), https://doi.org/10.46298/jdmdh.5759. ↩︎

Ben Brumfield, “The Decade in Crowdsourcing Transcription,” FromThePage (blog), January 9, 2020, https://content.fromthepage.com/decade-in-crowdsourcing/. ↩︎

Victoria Van Hyning, “Finding By the People Transcriptions in the Library’s Digital Collections,” The Signal (blog), Library of Congress, July 9, 2020. https://blogs.loc.gov/thesignal/2020/07/finding-by-the-people-transcriptions-in-the-librarys-digital-collections/. ↩︎

Stats are updated monthly at https://crowd.loc.gov/about/. ↩︎

“PastPerfect Museum Software” PastPerfect Museum Software. 2021. https://museumsoftware.com/. ↩︎

Section 508 of the Americans with Disabilities Act “establishes requirements for electronic and information technology developed, maintained, procured, or used by the Federal government. Section 508 requires Federal electronic and information technology to be accessible to people with disabilities, including employees and members of the public.” - https://www.ada.gov/cguide.htm ↩︎